Livres anciens et modernes

SEBASTIANI MINTURNO, Antonio (ca. 1497-1574)

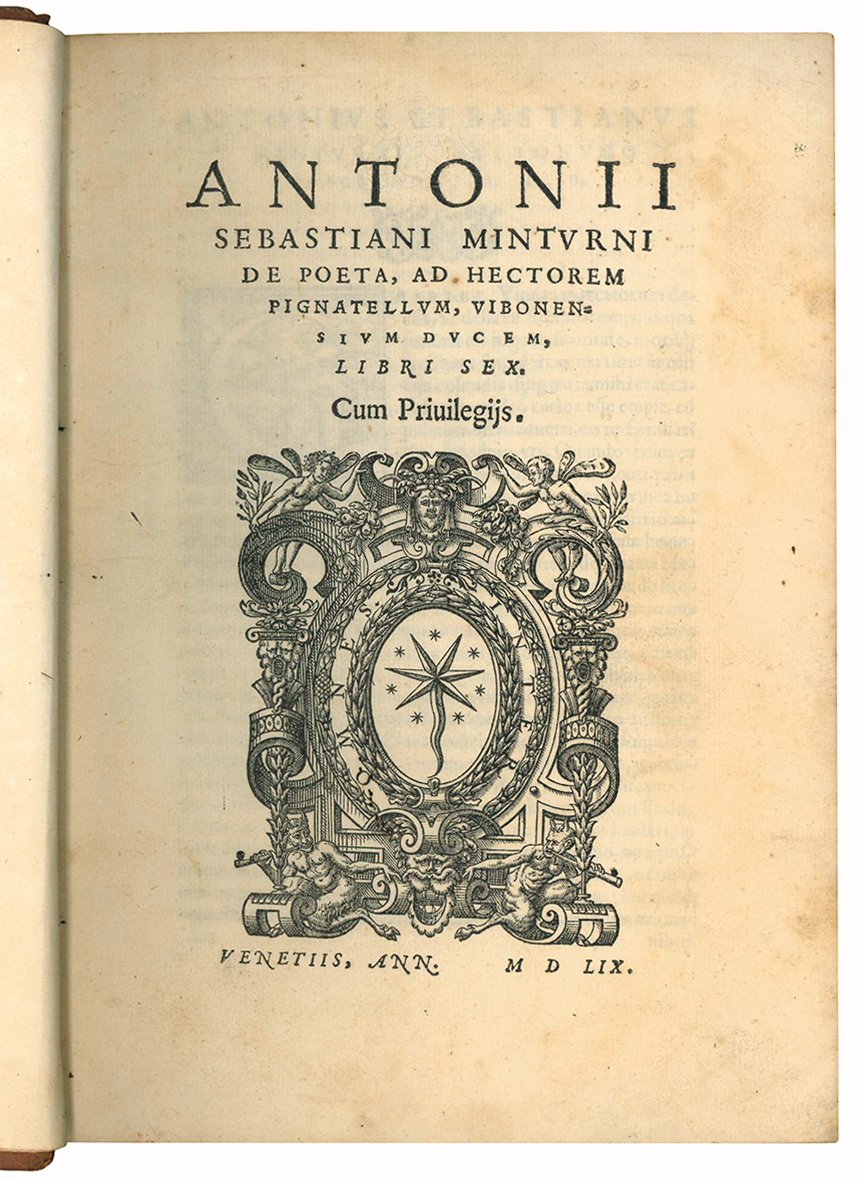

De poeta, ad Hectorem Pignatellum, Vibonensium ducem, libri sex

(Francesco Rampazetto [for Giordano Ziletti]), 1559

1500,00 €

Govi Libreria Antiquaria

(Modena, Italie)

Les frais d'expédition corrects sont calculés une fois que l'adresse de livraison a été indiquée lors de la création de la commande. Un ou plusieurs modes de livraison sont disponibles à la discrétion du vendeur : standard, express, economy, in store pick-up.

Conditions d'expédition de la Librairie:

Pour les articles dont le prix est supérieur à 300 euros, il est possible de demander un plan de paiement échelonné à Maremagnum. Le paiement peut être effectué avec Carta del Docente, Carta della cultura giovani e del merito, Public Administration.

Les délais de livraison sont estimés en fonction du temps d'expédition de la librairie et de la livraison par le transporteur. En cas de retenue douanière, des retards de livraison peuvent survenir. Les frais de douane éventuels sont à la charge du destinataire.

Pour plus d'informationsMode de Paiement

- PayPal

- Carte bancaire

- Virement bancaire

-

-

Découvrez comment utiliser

votre Carta del Docente -

Découvrez comment utiliser

votre Carta della cultura giovani e del merito

Détails

Description

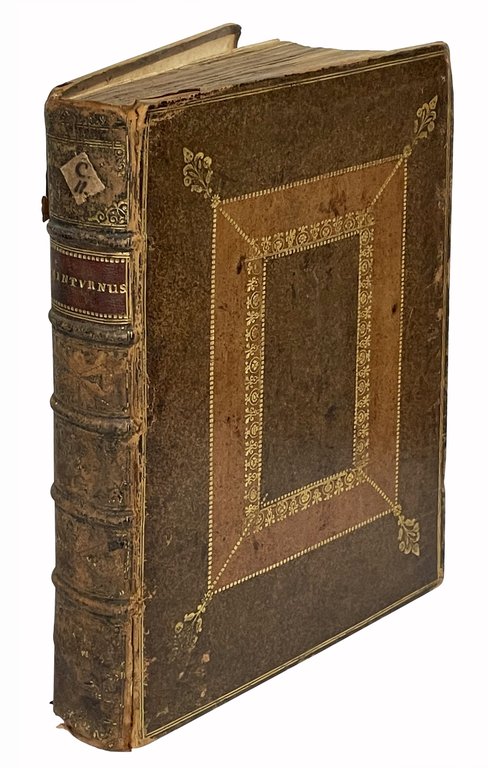

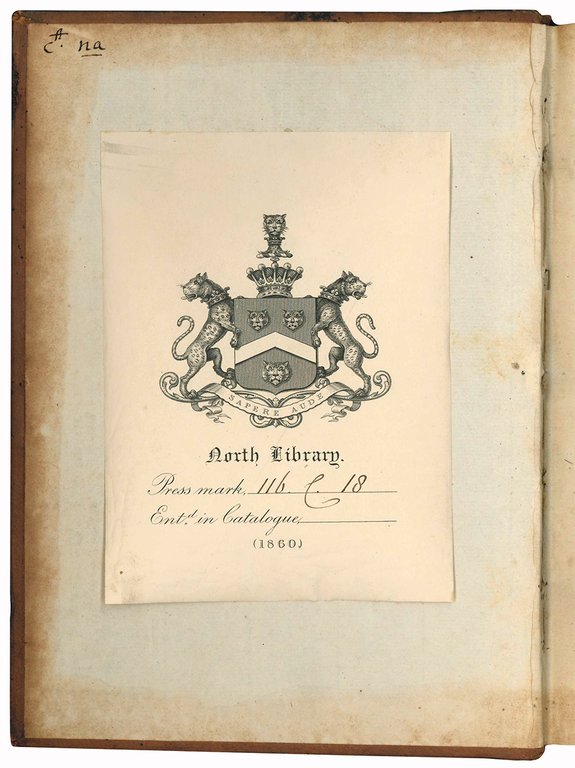

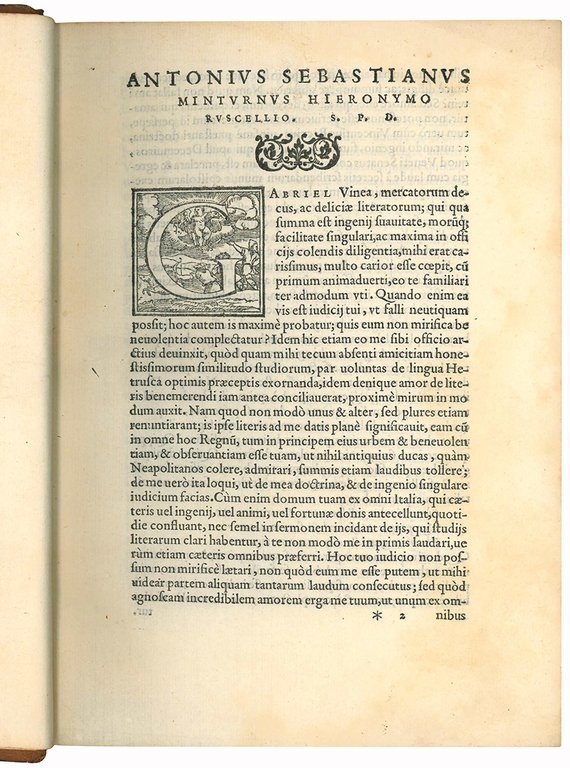

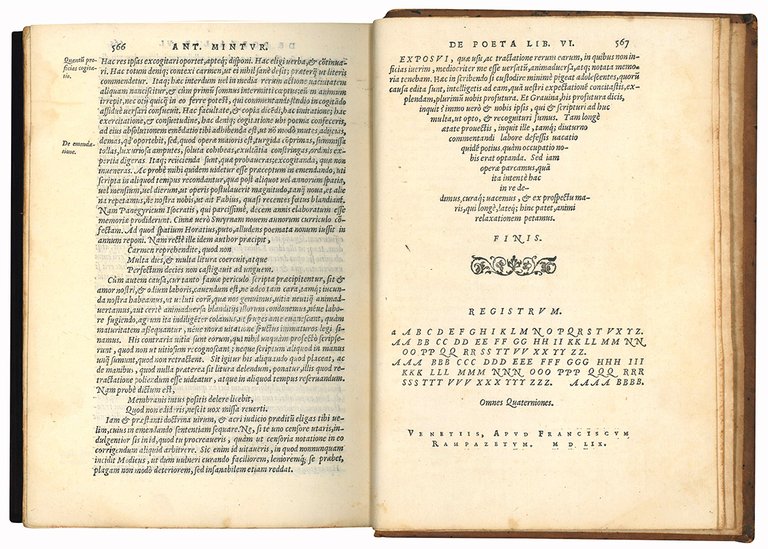

4to (205x145 mm). [8], 567, [1 blank] pp. Collation: *4 A-BBBB4. Ziletti's device on title page. 18th-century panelled calf gilt, spine gilt in compartments, red morocco lettering piece, sprinkled edges (extremities and spine rubbed). On the front pastedown engraved bookplate of the Earls of Macclesfield (cf. The Library of the Earls of Macclesfield, Part Twelve, London, Sotheby's, 2008, no. 4619). A very good copy.

First edition. “In comparison with its fairly short, fairly meager, fairly single-minded predecessors, Antonio Sebastiano Minturno's De poeta (1559) is a colossus among ‘artes poeticae'. The six books of dialogue make an aggregate of almost six hundred pages. Besides, rather than drawing almost exclusively upon the Ars poetica, the work incorporates (in addition to Horace) almost all of the Poetics and abundant materials from Plato (Republic, Laws, Ion, etc.), from Aristotle's Rhetoric, from Quintilian, and from all the rhetorical writings of Cicero. It is thus the first of the really extensive arts of poetry, the first to attempt a detailed discussion of every aspect of doctrine and technique, the first to broaden considerably the range of references and ‘authorities'. These features are not without important consequences for the nature of the work itself; for they give to it a wide-ranging eclecticism, which is reflected in the theory ultimately evolved by Minturno […] From the way these various distinctions are developed, from the miscellaneous shutting off in the directions of the poet or nature or the poem or the audience, it should be clear the Minturno's treatise remains primarily eclectic and syncretic. None of the term of ultimate reference comes to dominate the others, to impose a systematic organization upon the work. Insofar as there is any ordering of ideas, it is an ordering to rhetorical principles. At one end of each of the chains of relationship is an effect upon the audience; at the other end, some faculty of the poet capable of producing that effect; in the middle, the poem serving as a means or instrument […] For Minturno, the poet, his art, and his faculties occupy a similar position of pre-eminence. What Minturno does, essentially, is to take over the whole rhetorical schematism of his times, to substitute for the orator the poet, and to introduce - at what seemed to him to be the most likely points in the argument - all the know materials on the art of poetry. In this way both the Poetics and the Ars poetica are, if not assimilated, at least incorporated into a vast compendium on the art” (B. Weinberg, A History of Literary Criticism in the Italian Renaissance, Chicago-Toronto, 1961, pp. 737-743).

Antonio Sebastiani was born in Minturno, near Latina, around 1497. In 1511 he moved to Sessa Aurunca to study with Agostino Nifo, whom he then followed to Padua and Pisa, where, by the end of 1520, he became a lecturer in poetics and oratory. At the end of 1521 he moved on to Rome as a lecturer in theology and philosophy. In Rome, thanks perhaps to the intercession of another student of Nifo, Galeazzo Florimonte, he came into contact with Ludovico Beccadelli, Girolamo Seripando, Gasparo Contarini and Filippo Gheri, later secretary to Cardinal Giovanni Morone. In 1524 he took up service as tutor to the Colonna family in Genazzano, and it was around this time that he entered the Order of the Theatines. The following year he returned to Naples to resume his studies; there he used to hang out with Girolamo Carbone, Pomponio Gaurico, Pietro Summonte, Pietro Gravina, and noblewomen such as Maria di Cardona, Giulia Gonzaga and Beatrice d'Appiano d'Aragona. It is very likely that in this period he adopted the name Minturno (from Minturnae, the Latin name of his hometown), which conferred a humanistic gravitas to his person. From October 1527 he was tutor first in the household of Camillo Pignatelli, count of Borrello, and later of Girolamo and Fabrizio Pignatel