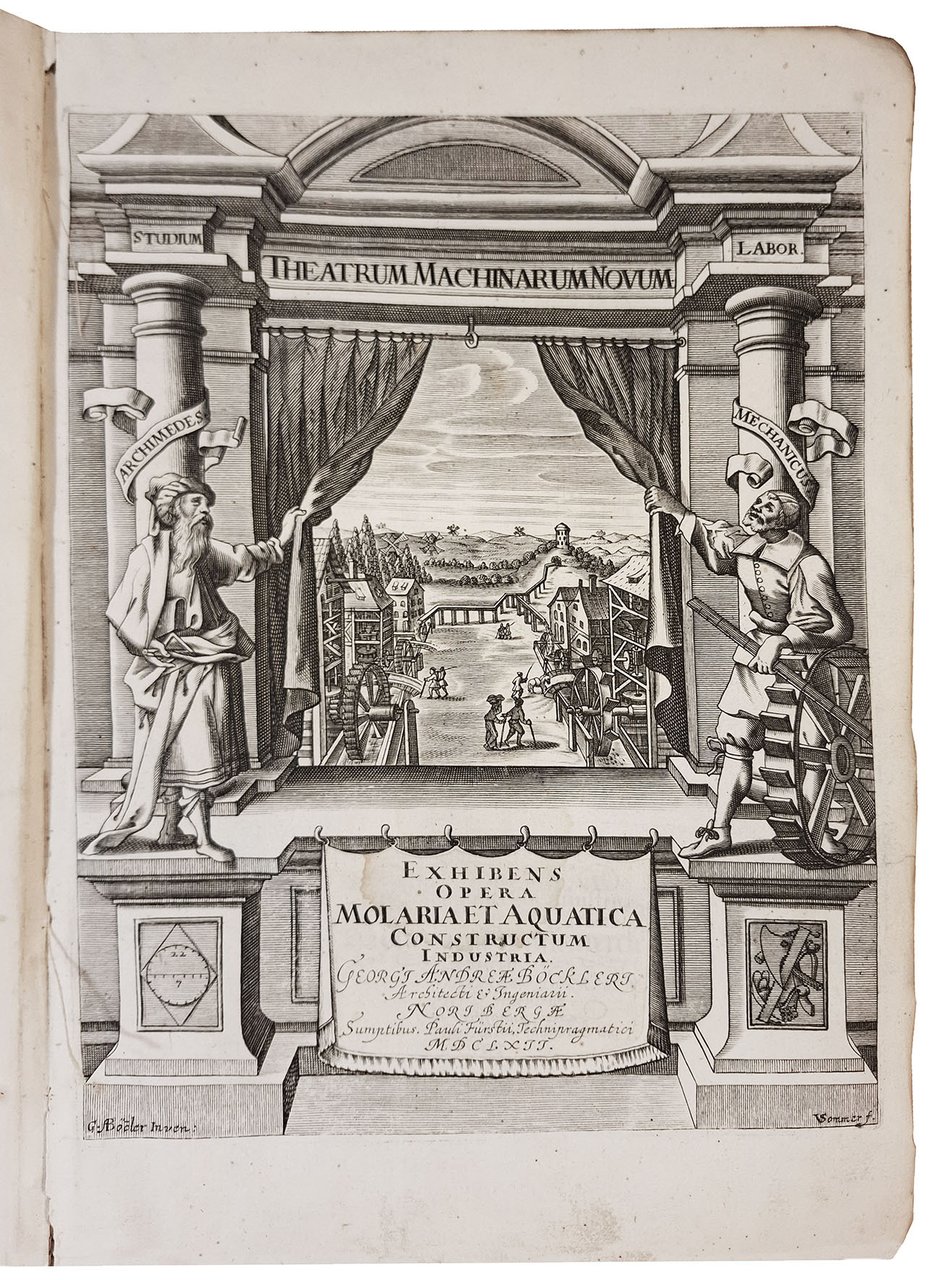

Theatrum machinarum novum, exhibens aquarias, alatas, iumentarias, manuarias; pedibus, ac ponderibus versatiles, plures, et diversas molas [...] Per Georgium Andream Bocklerum, architectum & ingeniarum. Ex Germania in Latium recens translatum opera R.D. Henrici Schmitz, [...]

Theatrum machinarum novum, exhibens aquarias, alatas, iumentarias, manuarias; pedibus, ac ponderibus versatiles, plures, et diversas molas [...] Per Georgium Andream Bocklerum, architectum & ingeniarum. Ex Germania in Latium recens translatum opera R.D. Henrici Schmitz, [...]

Mode de Paiement

- PayPal

- Carte bancaire

- Virement bancaire

- Pubblica amministrazione

- Carta del Docente

Détails

- Année

- 1662

- Lieu d'édition

- Köln

- Auteur

- BÖCKLER, Georg Andreas (1617-1687)

- Éditeurs

- Paul Fürst

- Thème

- seicento

- Etat de conservation

- En bonne condition

- Langues

- Italien

- Reliure

- Couverture rigide

- Condition

- Ancien

Description

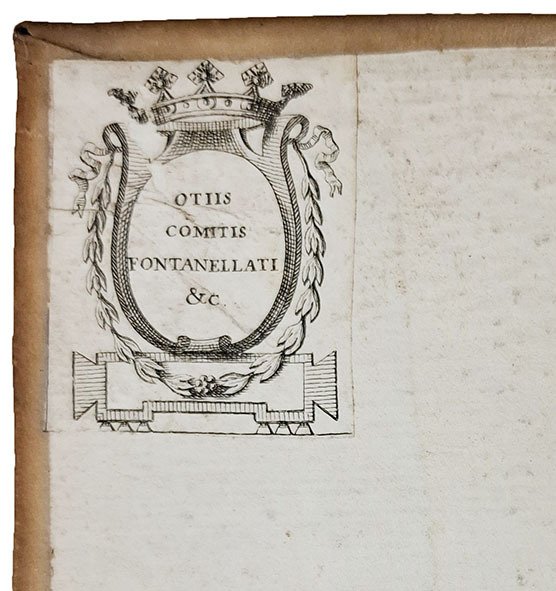

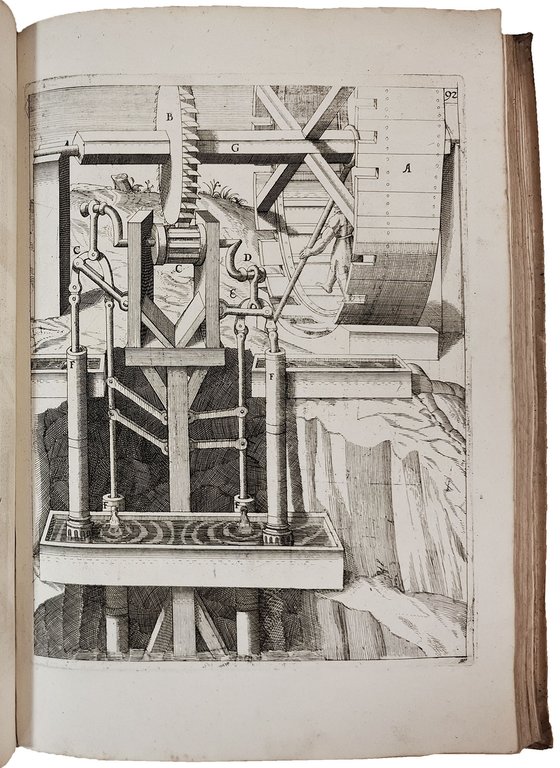

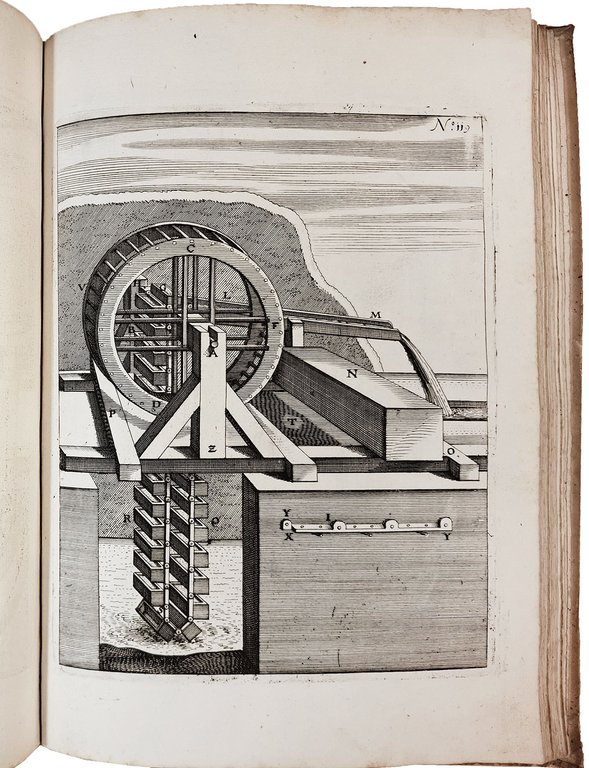

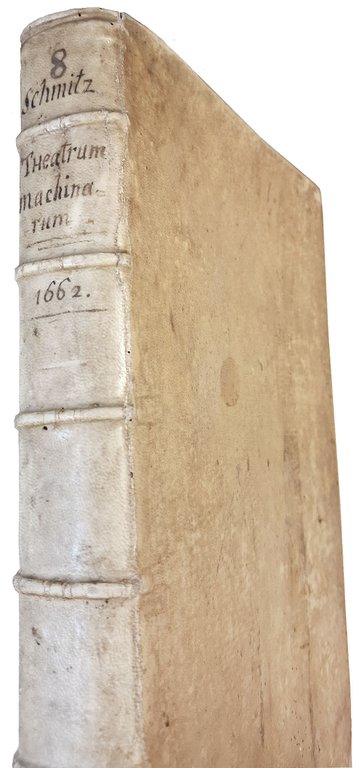

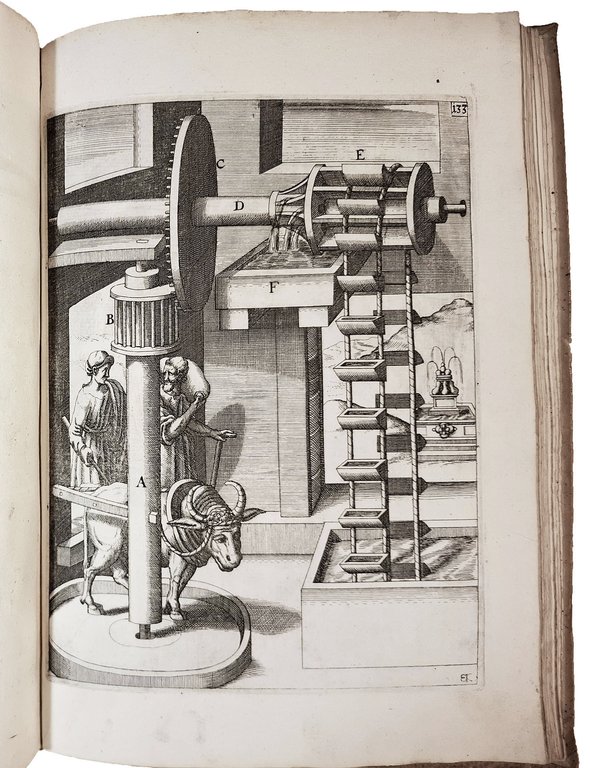

Folio (330x220 mm). Engraved title-page (Noribergae, sumptibus Pauli Furstii, technipragmatici, 1662), [10], 55, [1 blank] pp. and 154 full-page plates engraved by Eberhard Kieser and Balthasar Schwan after drawings by Böckler himself. Collation: ¶4-¶¶1 A-G4. Contemporary stiff vellum, spine with five raised bands and ink title. On the front pastedown engraved bookplate “Otiis comitis Fontanellati &c” of Alessandro Sanvitale di Fontanellato (1731-1804), founder of the Accademia degli Erranti in Fontanellato. Some occasional light browning and staining, small loss of paper to the outer blank corner of pl. 39 and 49. A very good, unpressed and genuine copy.

First Latin edition, in the translation by Heinrich Schmitz, of one of the most accomplished and successful 17th-century machine books. It first appeared in German at Nuremberg in 1661. The Latin edition was reprinted in 1686, the German edition in 1673, 1703 and 1705.

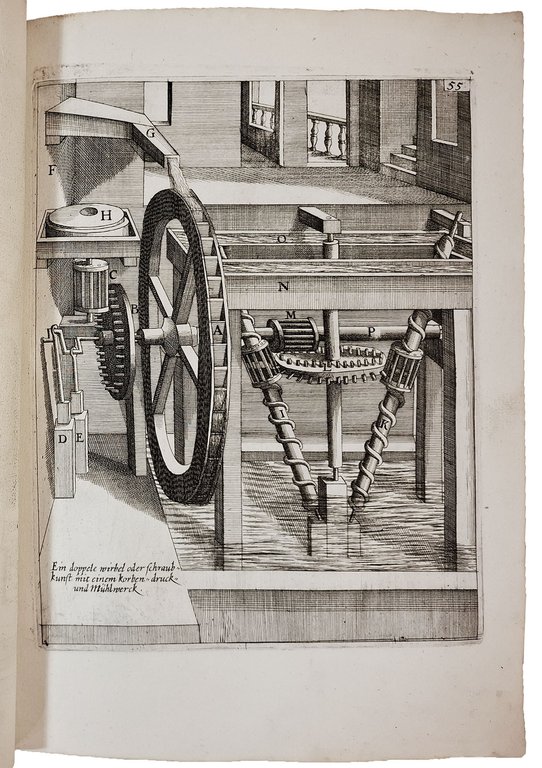

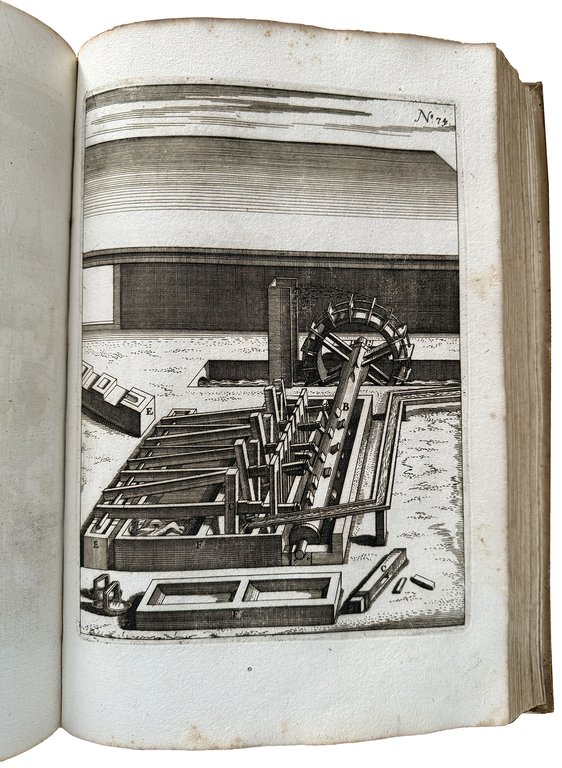

“It was in Germany that two of the most eminent engineering visionaries lived. The first of these was Georg Andreas Böckler who published a truly remarkable book […] called Theatrum Machinarum Novum, written and illustrated as a record of the progress of the art of engineering […] As one might gather, not just from the title page but from a knowledge of the general conditions pertaining in Germany after the Thirty Years' War, Böckler's acquaintance with machinery was restricted almost entirely to mills of one sort or another. In most of these, regardless of the motive power, he depicts the precursor of the geared transmission familiar to this day. The seventeenth-century engineers had neither the theoretical knowledge nor the technical equipment to design and shape gear-wheels which would mesh with minimum friction. In fact, friction as such, although made use of in such applications as the sack-lift in a mill, was little understood. The construction of pinions to mesh with larger gear-wheels had yet to assume the form common today. However, the problem of shifting the direction of rotation of a drive through 90° was solved by the invention of the wallower driven either by a contrite wheel (a wooden wheel with tooth pegs protruding around the circumference parallel to the axis) or by a cogwheel having teeth projecting radially around the circumference at right-angles to the axis […] The wallower comprised two discs of wood, each drilled with a matching set of concentric holes near the perimeter. The discs, usually with square centre bores to aid fixing and to transmit rotary motion, were mounted on a shaft separate by a gap of as much as the mechanism dictated, and threaded through the holes, from one disc to the next, were wooden rods. The result looked not unlike a birdcage or lantern, hence its more common name. When it was meshed with a large wheel having suitably spaced wooden pegs around either its diameter (the contrite) or its periphery (the cog), depending on whether parallel or perpendicular motion was desired, a serviceable gear train was the result. Friction, though cut efficiency drastically. All this is depicted in Böckler's Theatre of New Machines, but what is a far more striking feature of the illustrations is the constant recurrence of the germ of perpetual motion” (Arthur W.J.G. Ord-Hume, Perpetual Motion. The History of an Obsession, Kempton IL, 2005, pp. 47-48).

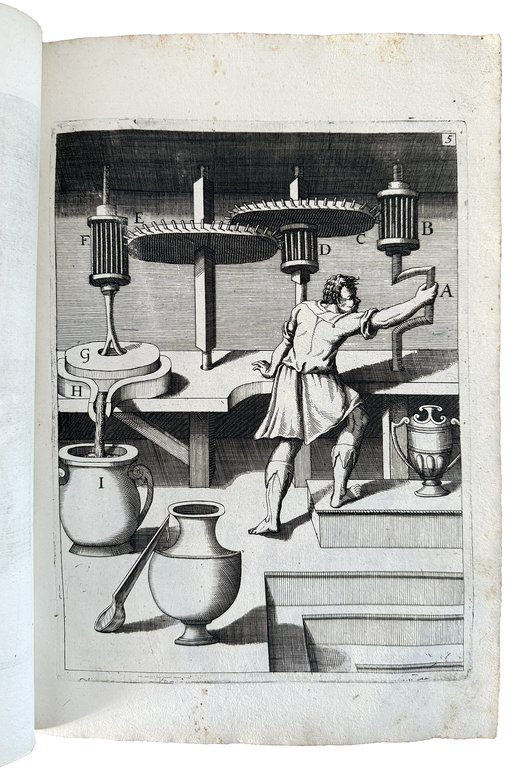

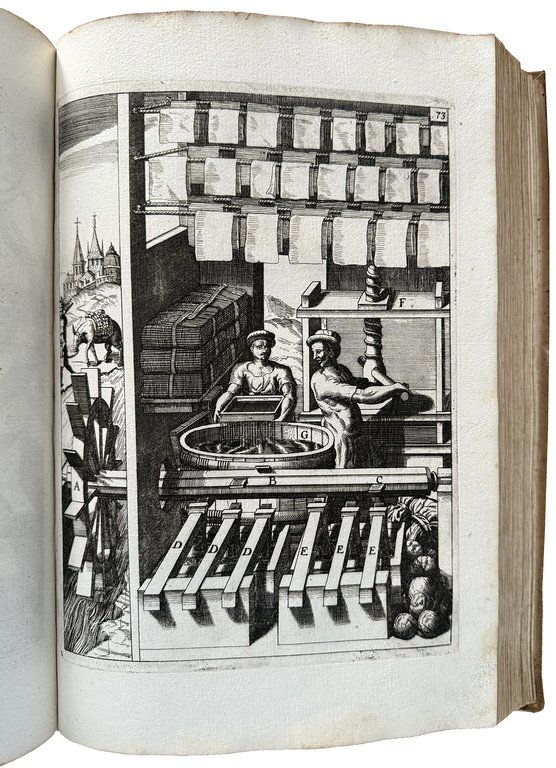

The strongly inked plates show hydraulic and mechanical machines powered by intricate systems of wheels that employ water, wind, weights, animal or human power, or some combination of these. These machines include many curious inventions applicable to all trades and human activities, such as paper and grain mills, drilling machines, roasting machines, water pumps, wood saws, blowing machines, fire engines, roasting spits, and so on.

In particular, plate 5 pictures a hand mill for making ink for copperplate printing; plates 34, 36, 37, 41, 46, 47, and 59 depict mills used for grinding flour and sharpening stones, tools and knives;