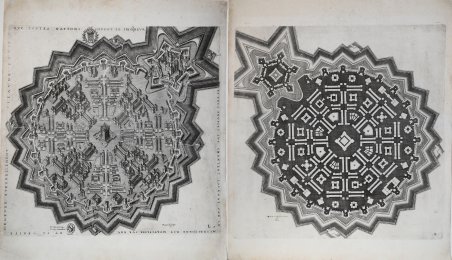

Acquaforte, numerata in basso a destra “L”, scala in basso a sinistra, scala grafica espressa in Toises. Impressa su carta vergata coeva filigranata, ampi margini, in ottimo stato di conservazione. Dimensioni lastra: 402 x 407.Planimetria della cittadella ugonotta mostrata nella seconda incisione.Acquaforte, numerata in basso a destra “L2”, accanto la firma “Thomas de Leu Sculpsit”. A sinistra “En Dieu Seul Repos/ Et Vray contentement” con accanto l’excudit di Perret.L’incisione mostra una città poligonale regolare difesa da ventitré bastioni, coronata da una cittadella pentagonale e ricca di strutture religiose, civili e domestiche. Intorno corre un Salmo, 117, che racchiude una concezione calvinista della società, del suono e dello spazio “QVE TOVTES NATIONS LOVENT LE SEIGNEVR ET TOVS PEVPLES LVY CHANTENT LOVANGE CAR SA MISERICORDE EST MVLTIPLEE SVR NOV ET SA VERITE DEMEVRE ETERNELLEMENT PSEAVME CXVII”.In questo quadro teologico, è interessante notare la relazione - o la sua mancanza - tra le strutture di Perret e i contesti circostanti. I trattati di fortificazione di successo, come le tanto apprezzate opere di Francesco de' Marchi e Jean Errard, non erano semplici esercizi teorici: i loro principi geometrici idealizzati dovevano essere adattabili alle specificità dei luoghi reali, ma Perret distingue esplicitamente la propria opera da questi trattati: "Pour ce que plusiers ont écrit des principes de géométrie, fortifications, architecture et perspective, je n'en met point en ce livre". Nonostante le loro somiglianze formali con le strutture di Perret, le fortezze di Errard sono enfaticamente piantate in uno spazio fisico reale.Le città fortificate di Perret sembrano invece galleggiare sulla superficie della carta, descrivendo una "geografia" religiosa alternativa. Richiamano il commento neoplatonico di Calvino al Salmo 117, che descrive una natura che, nonostante la sua insensibilità, sembra parlare. Perché se le "creature razionali" cantano le lodi verbali, lo "Spirito Santo altrove chiama le montagne, i fiumi, gli alberi, la pioggia, i venti e i tuoni a risuonare le lodi di Dio, perché tutta la creazione lo proclama silenziosamente come suo Creatore". " Per i lettori moderni, le città "ideali" delle Fortificazioni possono apparire come disegni tecnici, anche se di alto valore estetico, ma per i lettori ugonotti dell'epoca, queste strutture - accoppiate con le iscrizioni sacre circostanti - avrebbero trasmesso un significato emotivo completamente diverso. Calvino rifiutò deliberatamente l'accademismo arido, ponendo la musica al centro della sua teologia per il suo potere di favorire l'interiorizzazione soggettiva della Parola.L’opera di Perret,” Des Fortifications et artifices architecture et perspective. [I edizione Parigi, s.n. ma1601] dedicata a Enrico IV, è suddivisa in tre temi principali: città e cittadelle ideali fortificate, architettura religiosa e architettura privata. Questo miscuglio di generi, architettura militare e religiosa, non ha precedenti nella storia dei trattati di fortificazione. Le 22 superbe tavole che lo corredano – come anche il frontespizio – sono opera del famoso incisore protestante Thomas Le Leu (1555-1612). Rappresentano città fortificate o "città ideali" e consistono in una planimetria o in una pianta in elevazione e prospettiva accompagnata da note scritte da Perret. Le piante sono circondate da iscrizioni bibliche tratte in gran parte dai Salmi. In realtà, sotto l’apparenza di un testo tradizionale sulle fortificazioni urbane, propone modelli di cittadelle riformate, secondo geometrie stellari a 16 o 24 punte, articolate da complessi residenziali radiali e incentrate su un’alta sala di culto ugonotta. Etching, numbered at bottom right "L", scale at bottom left, graphic scale expressed in Toises. Imprinted on contemporary watermarked paper, large margins, in excellent condition. Sheet dimensions: 402 x 407.Planimetry of the Huguenot Citadel shown in the second plate.Etching, numbered "L2" on the bottom right, next to the signature "Thomas de Leu Sculpsit". On the left "En Dieu Seul Repos/ Et Vray contentement" with Perret's excudit next to it. Printed on contemporary laid paper, large margins, in excellent condition.Encircling the fortress—a regular polygonal city defended by twenty-three bastions, crowned with a pentagonal citadel, and replete with religious, civic, and domestic structures—is a Psalm which encapsulates a Calvinist conception of society, sound and space.“QVE TOVTES NATIONS LOVENT LE SEIGNEVR ET TOVS PEVPLES LVY CHANTENT LOVANGE CAR SA MISERICORDE EST MVLTIPLEE SVR NOV ET SA VERITE DEMEVRE ETERNELLEMENT PSEAVME CXVII”The inclusion of this Psalm 117 into the Genevan Catechism’s 1545 Action de graces apr?s le repas would have burned these two lines into the consciousness of French-speaking Protestants. Its regular phenomenological iteration as ritual song before the communal breaking of bread committed the Psalm to individual and social memory through melody, language, public performance, and its relation to bodily sustenance. On a broader scale, the Psalm meshed with a theological conception of geographical conquest. In his commentary on the verses, John Calvin exhorts readers to take seriously the words that “toutes nations” will resound in praises to the true God: while not all Gentiles would become believers, those who did would “be spread over the whole world.” By their daily chanting or reading these verses, the Huguenots would enter into literal harmony with a physically expansive community of believers, as well as with the natural landscape itself.Given this theological framework, it’s interesting to note the relation—or lack thereof—between Perret’s structures and their surrounding contexts. Successful fortification treatises, such as the much-consulted works of Francesco de’ Marchi and Jean Errard, were not merely theoretical exercises: their idealized geometric principles had to be adaptable to the specificities of real sites. But Perret explicitly distinguishes his own work from these treatises: “Pour ce que plusiers ont écrit des principes de géométrie, fortifications, architecture et perspective, je n’en met point en ce livre.” Despite their formal similarities with Perret’s structures, Errard’s fortresses are emphatically planted in real physical space.Perret’s fortified cities instead appear to float on the paper’s surface, describing an alternative religious “geography.” They recall Calvin’s Neoplatonic commentary on Psalm 117, which describes a nature that, despite its insentience, seems to speak. For if “rational creatures” sing verbal praises, the “Holy Spirit elsewhere calls upon the mountains, rivers, trees, rain, winds, and thunder, to resound the praises of God, because all creation silently proclaims him to be its Maker.” For modern readers, the highly regularized “ideal” cities of the Fortifications may appear to be technical drawings, albeit of high aesthetic value, but for Huguenot readers of the time, these structures—coupled with the surrounding sacred inscriptions—would have conveyed an entirely different emotive meaning. Calvin deliberately rejected dry academicism, placing music at the heart of his theology for its power in aiding the subjective internalization of the Word.Published three years after the 1598 proclamation of the Edict of Nantes, the Huguenot architect’s treatise reveals a tight bond between notions of sound and territoriality during the French Wars of Religion. Inscriptions on Fortifications’ illustrated plates borrow scriptural verses co-translated into French by poet Clément Marot an. Cfr. Dusmenil, X, n. 96.

Découvrez comment utiliser

Découvrez comment utiliser