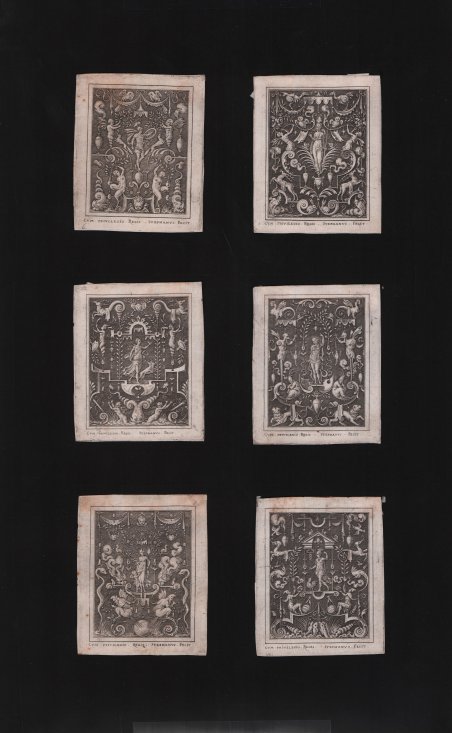

Serie completa di sei opere raffiguranti divinità romane, stampe grottesche su fondo scuro, con un Dio/Dea in piedi al centro di un’elaborata struttura abitata da delfini, figure femminili nude, erme alate e uccelli. Incisioni al bulino, circa 1570/72, firmate con nome dell'incisore l’indicazione di privilegio. Come dimostra la presenza del privilegio, la serie è stata incisa prima della partenza di Etienne Delaune dalla Francia (1572/73). A. Grottesca con Marte, B. Grottesca con Minerva, C. Grottesca con Diana, D. Grottesca con Apollo, E. Grottesca con Venere, F. Grottesca con Mercurio ' (in ordine di riga da sinistra a destra). Giorgio Vasari descrive come Giovanni da Udine portò Raffaello agli scavi della Domus Aurea dell'imperatore Nerone, dove videro “alcune stanze completamente sepolte sottoterra, che erano piene di piccole grottesche. che si chiamano grottesche per essere state scoperte nelle grotte sotterranee”. Tali pitture ornamentali erano state condannate nell'antichità. Il poeta Orazio le definiva “fantasie oziose. che hanno la forma dei sogni di un malato” e l’architetto Vitruvio pensava che questi ibridi fantasiosi potessero essere apprezzati solo da “menti ottenebrate da standard di gusto imperfetti”. Tuttavia, come i Romani che avevano “fantasie così varie e così bizzarre” che ornavano le loro pareti, Raffaello trovava “le loro piccole scene. piacevoli e belle”. Giovanni padroneggia la tecnica delle grottesche e insieme a Raffaello inizia a emularle in Vaticano e in altri progetti romani. Con l’imprimatur di Raffaello, questi ornamenti divennero un elemento di spicco del vocabolario all'antica associato al revival dell'antichità classica. Si diffusero rapidamente, tanto che alla fine del XVI secolo il saggista francese Michel de Montaigne osservava che, dopo aver completato un dipinto, “un pittore al mio servizio. [riempie] lo spazio vuoto tutt'intorno di grottesche; che sono quadri fantastici che non hanno altro fascino che la loro varietà e stranezza”. Le acqueforti e le incisioni furono il mezzo principale con cui i motivi grotteschi divennero onnipresenti. Le stampe degli italiani ispirarono i tipografi tedeschi, olandesi e francesi a inventare le proprie grottesche, che divennero modelli per gli artigiani che lavoravano con altri mezzi. Con il loro orientamento verticale, la simmetria bilaterale e i dettagli minuziosi, le Grottesche con divinità pagane di Delaune sono esempi eleganti di questo genere. Identificato dalla sua armatura, Marte (A) si erge precariamente su un'urna sostenuta da un'unica sottile asta. Gli vengono offerte corone di vittoria da putti i cui torsi terminano in spesse spirali. In alto, feroci rapaci presagiscono la vittoria, mentre in basso delfini con code a spirale affiancano una coppia di satire che guardano con ammirazione il dio. Anche Minerva (B), la dea della saggezza, si trova su un'urna. È affiancata da una coppia di farfalle e dalle civette che di solito la accompagnano. In alto, una coppia di uccelli-lumaca simili a struzzi e in basso cervi accoppiati, tritoni cornuti e conigli annidati nelle volute. Diana (C), con i suoi cani da caccia, la lancia e l'ornamento lunare, avanza all'interno di una curiosa cornice. In basso, una coppia speculare di donne nude sembra fuggire come se Adone si fosse appena imbattuto in loro mentre facevano il bagno. Due cervi con coda a spirale decorano gli angoli superiori e, sotto di loro, due donne, il cui fondoschiena termina con spirali decrescenti, suonano corni da caccia. Apollo (D) è in piedi con l'arco e la lira, affiancato da una coppia di creature dal becco appuntito montate su lame di spada rovesciate. Gli angoli superiori sono occupati da creature simili a sfingi; i leoni occupano gli angoli inferiori. Lumache, scorpioni, moscerini e uomini malinconici completano l'ornamento, che è messo in risalto dal denso sfondo monocromo che serve ad esaltare l'aspetto a rilievo otte. Complete set of six works representing Roman deities, grotesque prints on dark ground, with a God/Goddess standing in the middle of an elaborate structure inhabited by dolphins, naked female figures, winged herms and birds. Engravings, circa 1570/72, lettered with name of engraver and copyright line. As shown by the presence of the copyright, the set was engraved before Delaune's departure from France (1572/73). A. Grotesque with Mars, B. Grotesque with Minerva, C. Grotesque with Diana, D. Grotesque with Apollo, E. Grotesque with Venus, F. Grotesque with Mercury ' (in order of row from left to right). “Giorgio Vasari describes how Giovanni da Udine took Raphael to the excavations at the Emperor Nero's Golden House (Domus Aurea), where they saw "certain rooms completely buried underground, which were full of little grotesques. which are called grotesques from their having been discovered in the underground grottoes". Such ornamental paintings had been condemned in antiquity. The poet Horace characterized them as "idle fancies. shaped like a sick man's dreams," and the architect Vitruvius thought these fanciful hybrids could be appreciated only by "minds darkened by imperfect standards of taste". Nevertheless, like the Romans who had "fantasies so varied and so bizarre" ornamenting their walls, Raphael found "their little scenes. pleasing and beautiful". Giovanni mastered the technique behind the grotesques, and he and Raphael began to emulate them in the Vatican and other Roman projects. With Raphael's imprimatur, these ornaments became a prominent feature of the all’antica vocabulary associated with the revival of classical antiquity. They swiftly spread, so that by the end of the sixteenth century, the French essayist Michel de Montaigne observed that, after completing a painting, "a painter in my employment. [fills] the empty space all around with grotesques; which are fantastic paintings with no other charm than their variety and strangeness". Etchings and engravings were the primary means by which grotesque motifs became ubiquitous. Prints by Italians inspired German, Netherlandish, and French printmakers to invent their own grotesques, which became models for craftsmen working in other media. With their vertical orientation, bilateral symmetry, and minute detail, Delaune's Grotesques with Pagan Gods are elegant examples of this genre. Identified by his armor, Mars (A) stands precariously on an urn supported by a single slim rod. He is offered crowns of victory by putti whose torsos end in thick spirals. Above, fierce raptors presage victory while, below, dolphins with spiraling tails flank a pair of satyresses who look admiringly at the god. Minerva (B), the goddess of wisdom, also stands on an urn. She is flanked by a pair of butter- flies and the owls that usually accompany her. Above are a pair of ostrich-like snail-birds and below are paired stags, horned tritons, and rabbits that nestle in volutes. Diana (C), with her hunting dogs, spear, and moon ornament, strides forth within a curious frame. Below, a mirrored pair of nude women appear to flee as though Adonis has just come upon them bathing. Two spiral-tailed stags decorate the upper corners and, below them, two women, whose bottoms end in diminishing spirals, blow hunting horns. Apollo (D) stands with his bow and lyre, flanked by a pair of sharp- billed creatures mounted on inverted sword blades. The upper corners are occupied by sphinx-like creatures; lions fill the lower corners. Snails, scorpions, gnats, and melancholy men complete the ornamentation that is set off by the dense monochrome background that serves to enhance the relief-like appearance achieved by Delaune. Venus (E), the goddess of love and beauty, stands with her protective son, Cupid, and her doves. A flaming torch, flaming hearts, and flaming arrows are appropriately featured, although it is difficult to explain the presence of the snakes that balance on the tips of thei. Cfr.

Découvrez comment utiliser

Découvrez comment utiliser