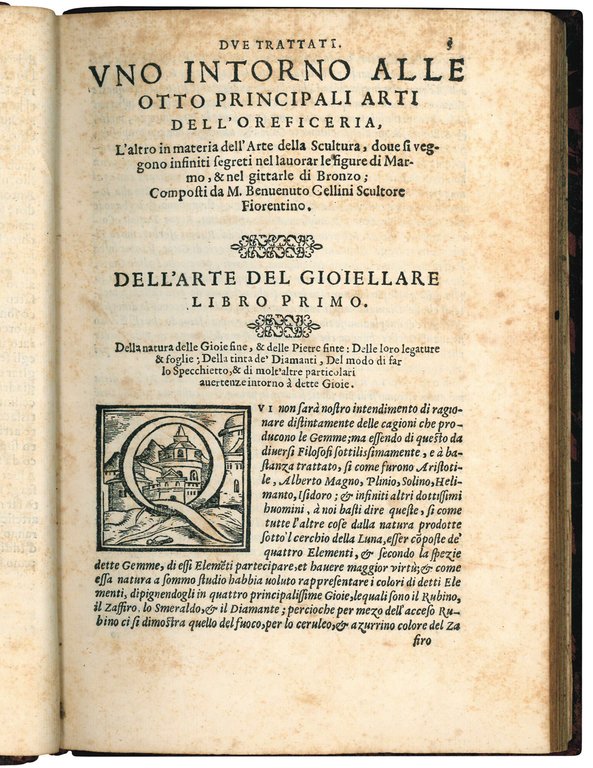

Due trattati uno intorno alle otto principali Arti dell'Oreficeria. L'altro in materia dell'Arte della Scultura; dove si veggono infiniti segreti nel lavorare le Figure di Marmo e nel gettarle in Bronzo

Due trattati uno intorno alle otto principali Arti dell'Oreficeria. L'altro in materia dell'Arte della Scultura; dove si veggono infiniti segreti nel lavorare le Figure di Marmo e nel gettarle in Bronzo | Libri antichi e moderni | CELLINI, Benvenuto (1500-1571)

Due trattati uno intorno alle otto principali Arti dell'Oreficeria. L'altro in materia dell'Arte della Scultura; dove si veggono infiniti segreti nel lavorare le Figure di Marmo e nel gettarle in Bronzo

Due trattati uno intorno alle otto principali Arti dell'Oreficeria. L'altro in materia dell'Arte della Scultura; dove si veggono infiniti segreti nel lavorare le Figure di Marmo e nel gettarle in Bronzo | Libri antichi e moderni | CELLINI, Benvenuto (1500-1571)

Metodi di Pagamento

- PayPal

- Carta di Credito

- Bonifico Bancario

- Pubblica amministrazione

- Carta del Docente

Dettagli

- Anno di pubblicazione

- 1568

- Luogo di stampa

- Firenze

- Autore

- CELLINI, Benvenuto (1500-1571)

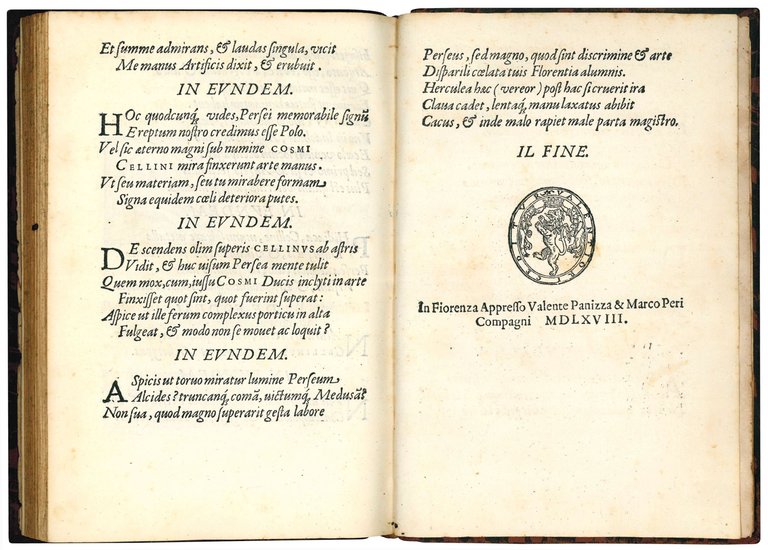

- Editori

- Valente Panizza & Marco Peri

- Soggetto

- Quattro-Cinquecento

- Stato di conservazione

- Buono

- Lingue

- Italiano

- Legatura

- Rilegato

- Condizioni

- Usato

Descrizione

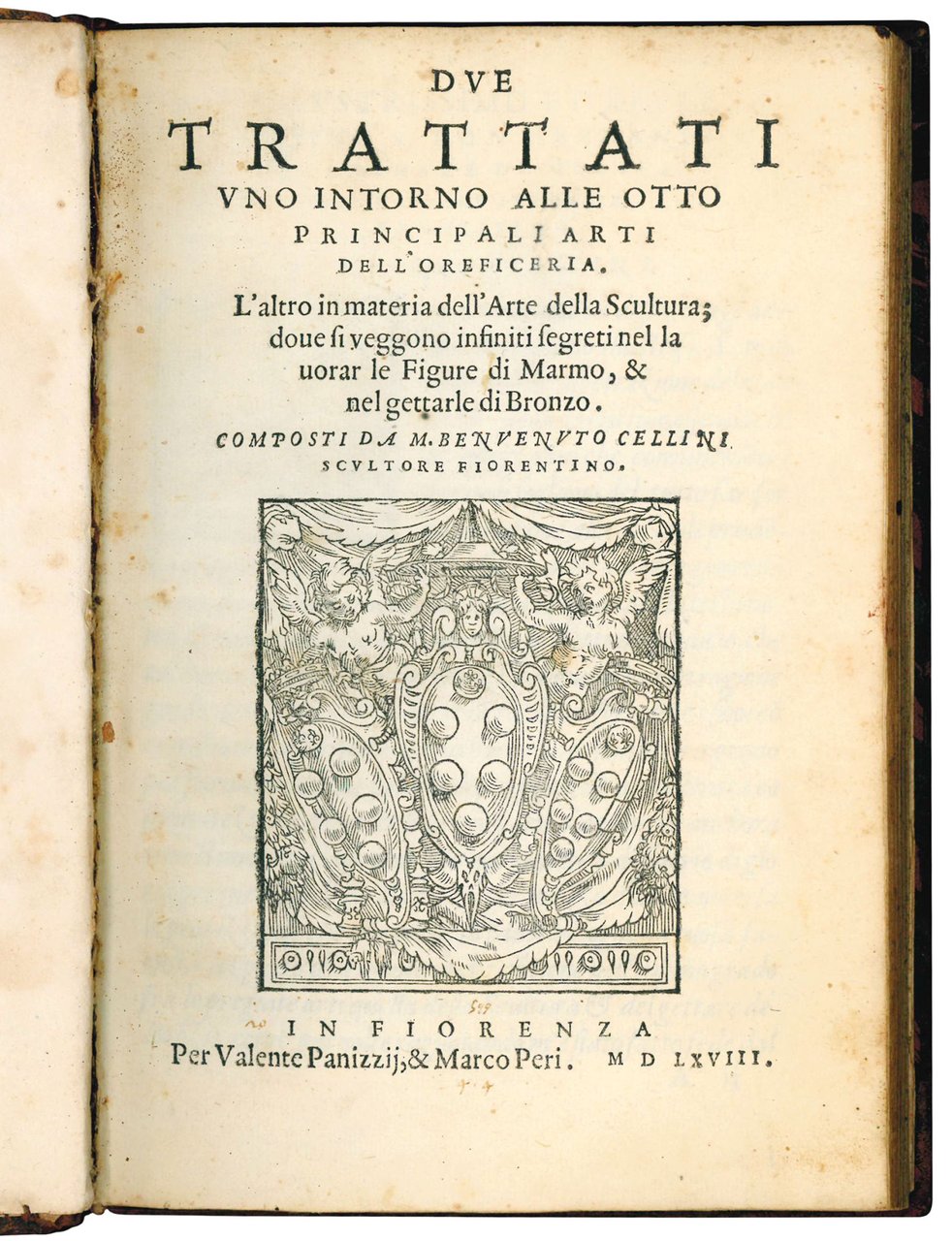

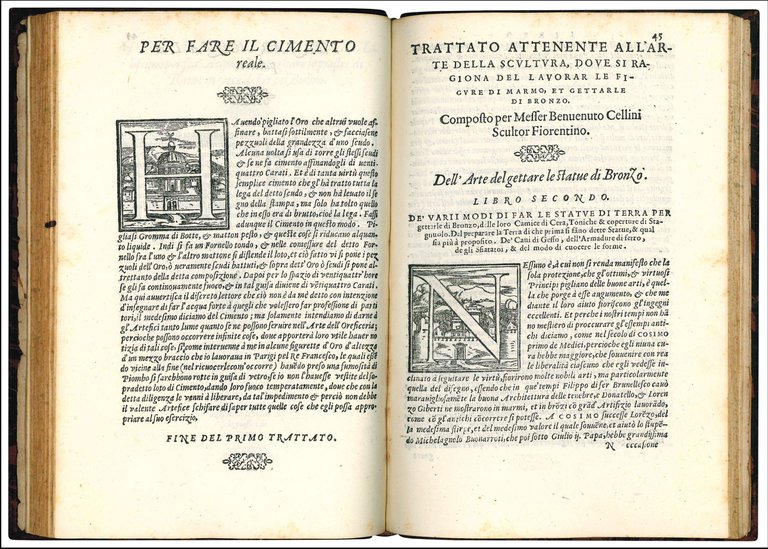

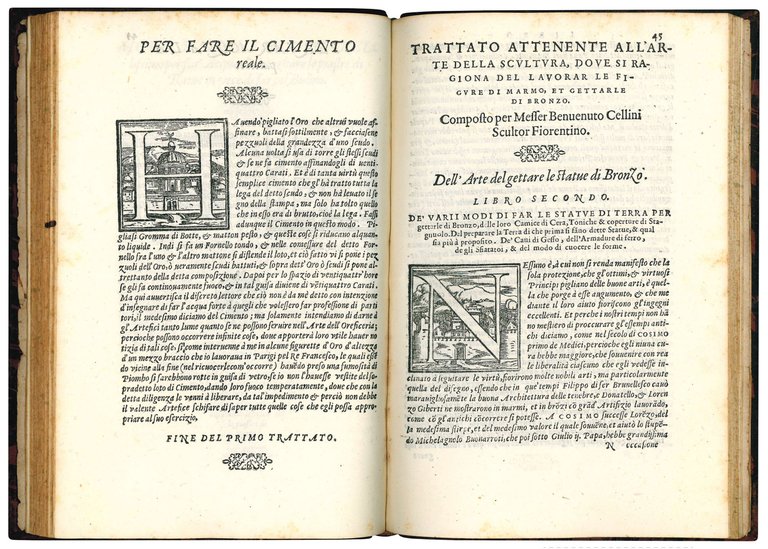

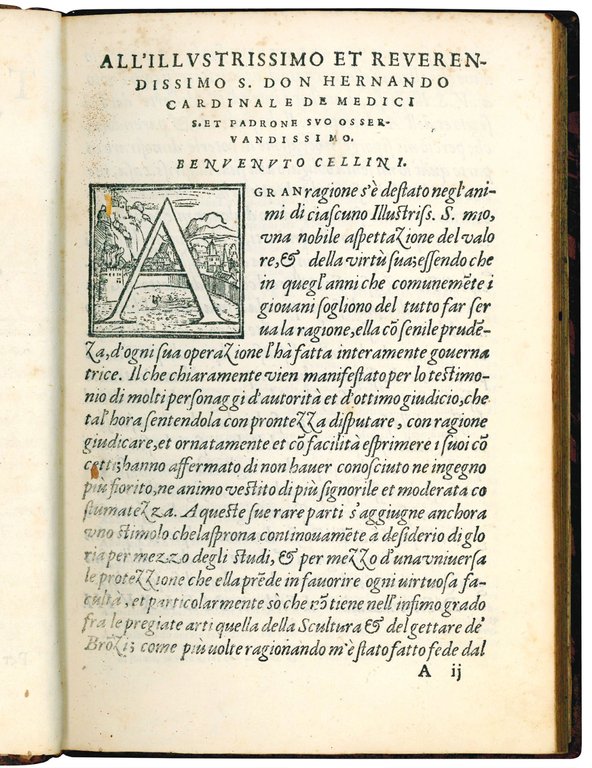

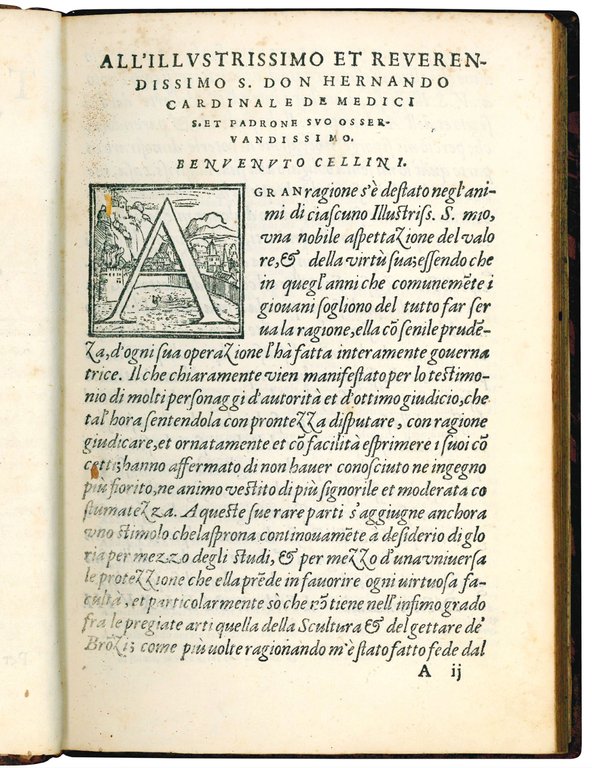

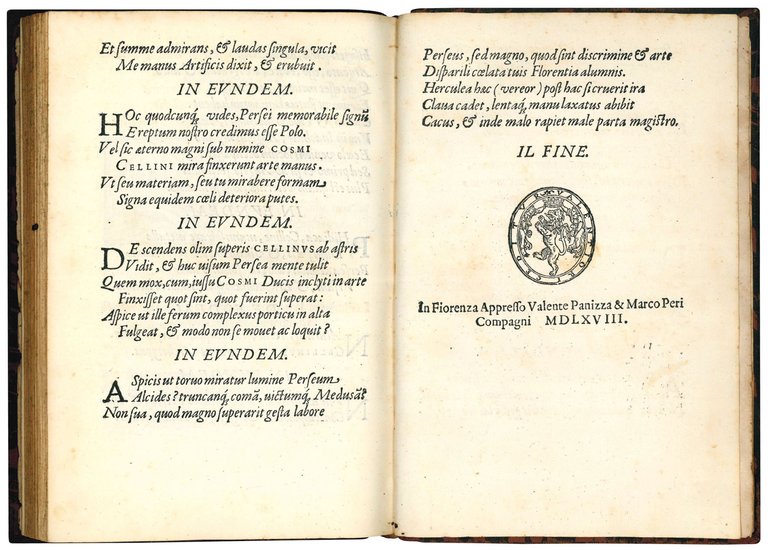

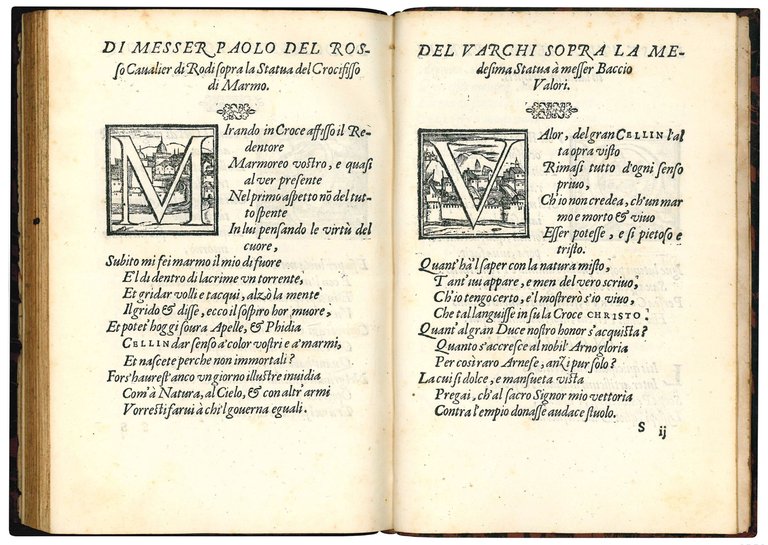

4to (213x141 mm). [5], 61, [7] leaves (ll. 26, 47, 51, and 61 are wrongly numbered). Collation: A6 B-S4 (leaves A6, B2v and S4v are blank). On the title page woodcut coat-of-arms of the dedicatee Ferdinando de' Medici. Colophon and Panizza's woodcut device on l. S4r. Woodcut head- and tail-pieces, and large woodcut historiated initials. 17th-century mottled calf, richly gilt spine with five raised bands, sprinkled edges (small worm holes to the hinges and spine, slightly worn and rubbed). On the front pastedown early 19th-century bookplate of Francesco Carafa della Spina (‘Ex libris Vinc. M. Kar.Ca.St. Pr. Amphiss. Scan. Plut. N.'), engraved by G. Cataneo. Some occasional foxing and browning, but a good, genuine copy.

First edition, dedicated to Cardinal Ferdinando de' Medici on 26 February 1568, of Cellini's two treatises on goldsmithing and sculpture, the only work published during his lifetime.

After the glorious moment following the unveiling of the Perseus statue in Piazza della Signoria in 1554, Cellini fell into disgrace at the Medici court, to the point that he complained that the Grand Duke not only no longer commissioned anything from him, but also prevented him from accepting commissions from outside Florence or moving elsewhere. In this climate of frustration, Cellini began writing an autobiography in 1558, which the following year he entrusted to his friend Benedetto Varchi for revision, but which never saw the light of day during his lifetime (it was only printed many centuries later, in 1728), both because of its strongly personalistic tone and its criticism of the Florentine power. Cellini therefore decided to interrupt the drafting of the Vita and to continue his new activity as a writer by writing the two Trattati, with which he hoped to rise again at the court and to show his artistic qualities.

The Due trattati contains detailed information on Cellini's most prestigious commissions, especially of jewellery, not found in his autobiography, such as the salt cellar for Francois I, the medal of Pope Clement VII, the seal of Cardinal Ippolito d'Este, and others. Cellini reveals the secrets and methods of designing medals, enamelling, minting coins, soldering, colouring diamonds, etc., and of the art of goldsmithing in general. The techniques of the Florentine sculptors of the ‘Quattrocento' are also discussed, like those of Donatello who attacked the block directly without the use of large-scale models. There is also a crucial passage on Michelangelo's sculpting technique: how he sketched the figure in charcoal on the block, how he made large-scale clay models, and what kind of chisels and drills he used.

Cellini's treatises were not republished until 1731 and were not translated until the 19th century. The many secrets and invaluable practical advice he gives in the Trattati are still of the highest value to craftsmen today, offering a wealth of technical instructions drawn from the artist's direct experience. “In the last two decades of his life, he composed a lengthy and unfinished autobiography, more than one hundred vernacular poems, two treatises on goldsmithing and sculpture, and several discourses on art. Indeed, for a long time Benvenuto Cellini's fame rested on his accomplishments as a writer, rather than on the works he created as a goldsmith and sculptor” (D. Gamberini, Benvenuto Cellini, Oxford Bibliographies, 2024).

“Le deuxième argument qui laisse penser que Cellini s'autocensura dans la rédaction de la Vita concerne l'histoire éditoriale des Trattati qui, comme celle de la Vita, fut complexe, laborieuse et tourmentée. Ces traités furent édités en 1568 du vivant de l'artiste, mais sous une forme très différente de celle qu'il avait lui-même rédigée. On le constata lorsqu'on exhuma et publia au XIXe siècle un manuscrit des traités (grâce à Francesco Tassi), qui fut publié en 1857 par Carlo Milanesi, et lorsqu'on put le comparer au texte imprimé en 1568. Ce codex, qui date du XVIe siècle, est écrit