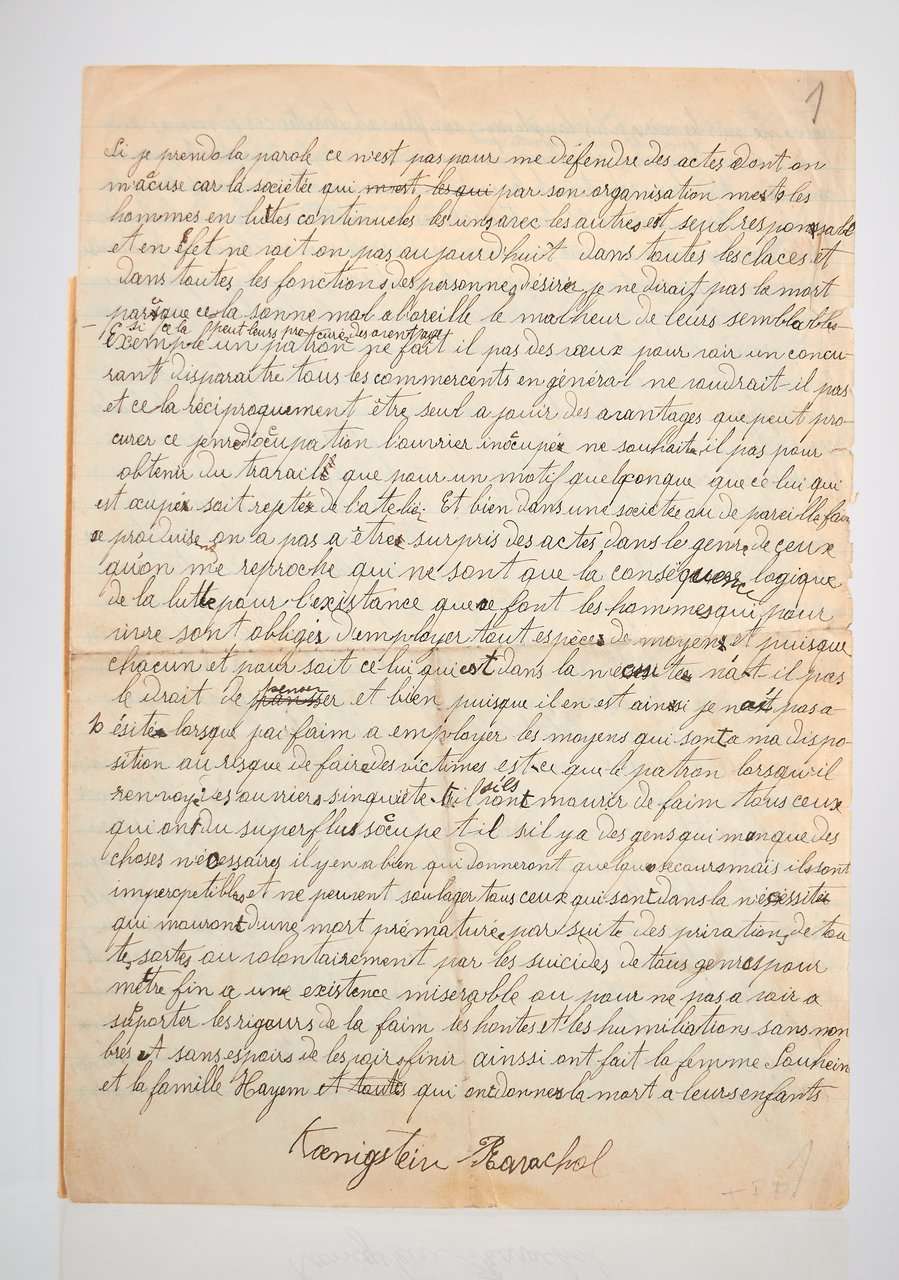

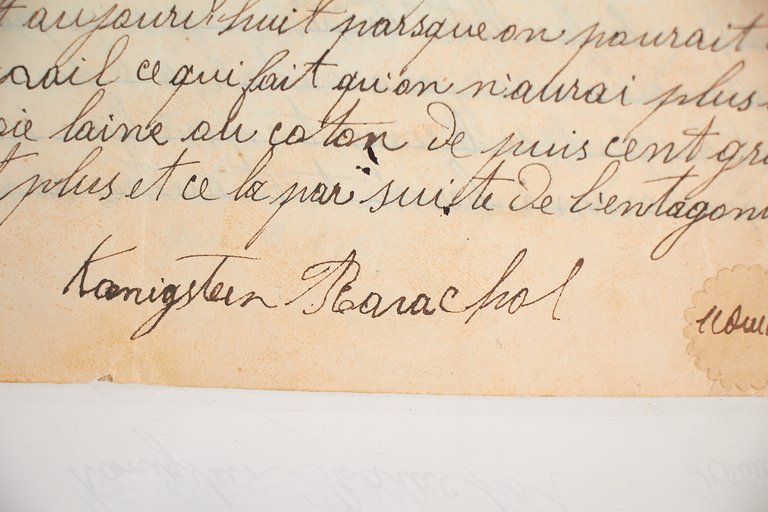

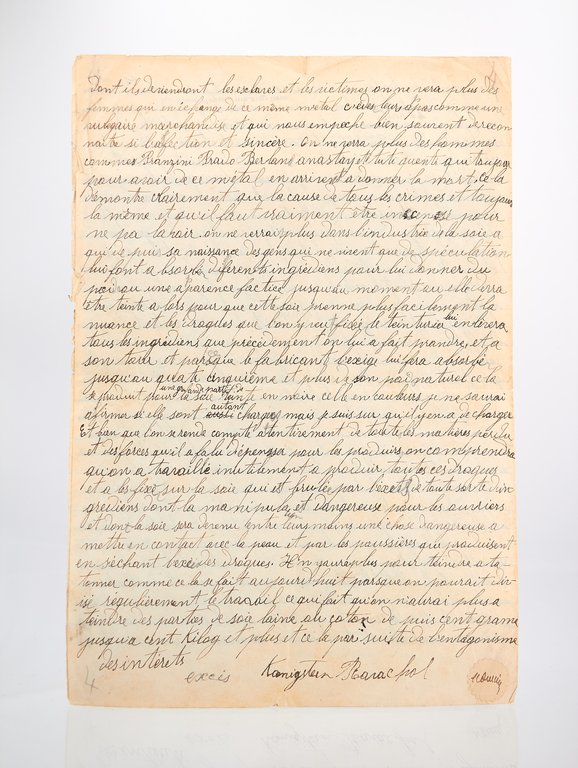

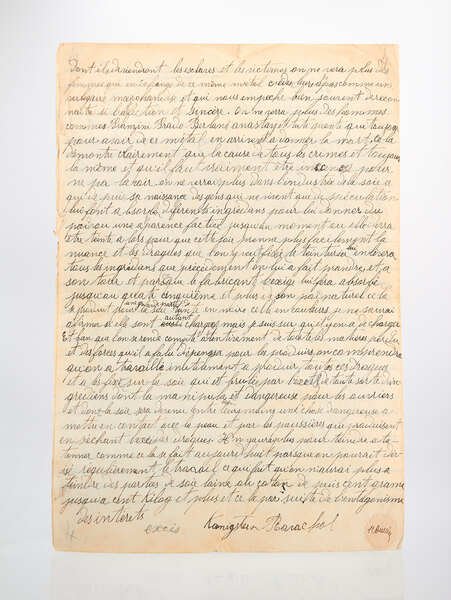

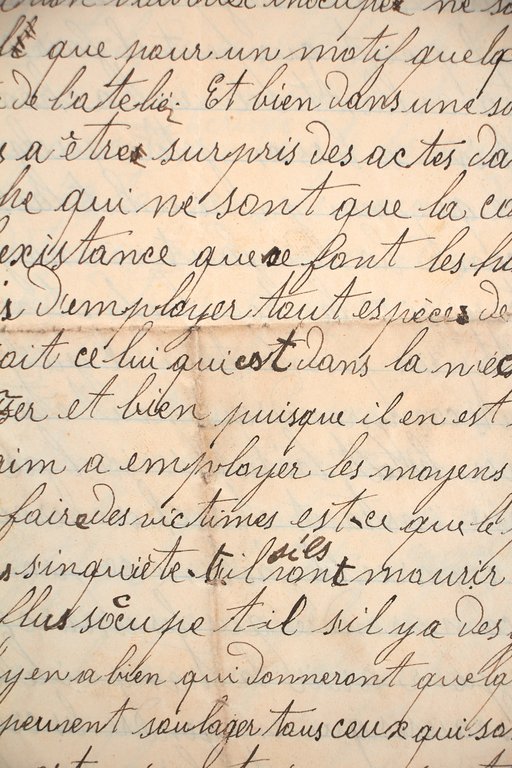

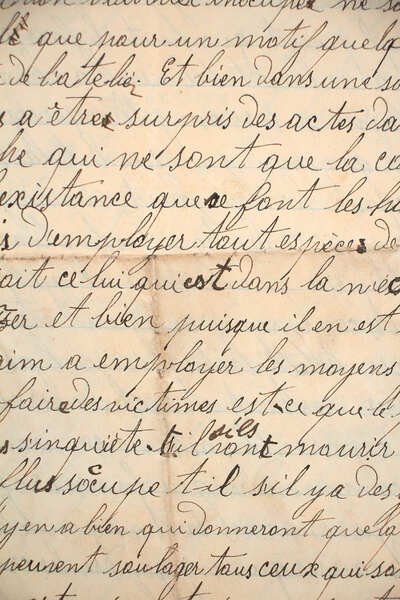

1892 | 20 x 29.50 cm | 4 pages sur un double feuillet | Exceptional complete autograph manuscript of Ravachol’s true last testament — largely unpublished — unknown in this form, preceding its rewriting by a third party for publication in the press. A unique testimony to the genuine thought of the anarchist icon. Four-page lined quarto manuscript, entirely written in black ink and signed twice “Konigstein Ravachol” at the foot of each sheet. Pencil corrections within the text, possibly in the hand of his lawyer. Some horizontal folds and very minor marginal tears, without loss. Written in his prison cell during the second Montbrison trial that led to his death sentence, this text, hastily penned, without punctuation or capital letters, and in naïve spelling, was meant to be delivered orally by Ravachol during the hearing. “Ravachol was dead set on putting in his two cents for the defence, not to defend himself, but to explain. No luck, dammit! Four words in and the judge cut him off. His statement isn’t lost, by Jove!” (Émile Pouget, in Père Peinard, July 3–10, 1892). This self-styled Rocambole of anarchism was not allowed to read his statement aloud, but he handed it to his lawyer Maître Lagasse, and by June 23 the forbidden text appeared in the conservative newspaper Le Temps. This first publication was so faithful to the original that it preserved the author's eccentric spelling — a fidelity that Émile Pouget would ironically criticise in the Père Peinard issue of July 3, 1892, one week before Ravachol’s execution: “Le Temps, that opportunist bedsheet, printed it as is. Like a true Jesuit, it even printed it too true. Ravachol had written the thing for himself; he knew how to read it — but there wasn’t a word of correct spelling, seeing as he knew about spelling as much as he knew about cabbage farming. Le Temps printed the thing without changing a line, so it’s practically unreadable [.]. That’s exactly what the bastards wanted, dammit! [.] I’m reprinting it below, without changing a word, just fixing the spelling.” That same July 3 issue of Père Peinard included a corrected version — orthographically — of the statement initially published in Le Temps. This dual publication, combined with Ravachol’s defiant bearing before the guillotine, had a powerful effect on public opinion. Until then, even anarchist publications had kept a certain distance from this provocative criminal, suspected of using the anarchist cause for personal gain. But following his execution, the testament was quickly reproduced in other newspapers, and Ravachol’s final cry of revolt soon became a genuine anarchist anthem among libertarians worldwide. However, the version circulated in the press — the only known version until now, the original manuscript having disappeared — differs markedly from the manuscript in our possession. Indeed, the style was lightly polished, several turns of phrase refined, and, most significantly, entire passages were excised, including the conclusion paragraph, which was fully replaced. Our manuscript, with its crossings-out and revisions, is likely the original version of this political testament. Written in a single burst, in dense handwriting, without punctuation or paragraph breaks, it includes two lengthy sections expressing concerns for public health that are entirely absent from the published version. The first is a third of a page-long passage about the “dangerous ingredients” added to bread: “no longer needing money to live, there’d be no fear of bakers adding dangerous ingredients to bread to make it look better or heavier, since it wouldn’t profit them, and they’d have, like everyone else and by the same means, access to what they needed for their work and existence. There’d be no need to check whether the bread weighs right, if the money is counterfeit, or if the bill is correct.” The second, nearly a full page long, concerns the silk-dyeing industry in which Ravachol had worked: “If one reflects atten

Descubre cómo utilizar

Descubre cómo utilizar