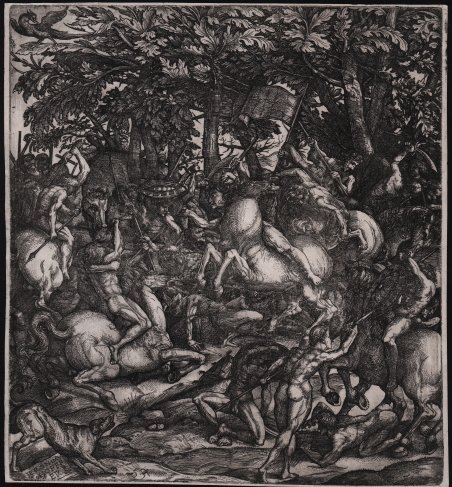

Battaglia di uomini nudi, con un combattimento tra cavalieri e fanti in una foresta. Copia del bulino di Domenico Campagnola (Hind 4) datato 1517. Acquaforte su ferro, 1550 circa, firmata nella lastra in basso a sinistra: “IERONIMU/S HOPFF/ER” (seguita dal simbolo di Hieronimus Hopfer). Copia incisa, abbastanza fedele, della Battaglia di uomini nudi di Campagnola. Le principali modifiche riguardano le foglie, che sono più grandi, più carnose, più numerose e più evidenti rispetto all'originale; in alto a sinistra è stato aggiunto un grande uccello appollaiato su una di queste foglie. L'opera è legata alle rappresentazioni di battaglie di Tiziano, tra cui la Battaglia del Cadore, oggi perduta, per il Palazzo Ducale di Venezia. La Battaglia di uomini nudi è una delle due incisioni più grandi e intriganti di Domenico Campagnola; per la gestione dei nudi, il trattamento del paesaggio e le azioni frenetiche delle figure, è anche tra i suoi disegni più caratteristici. Sebbene sia improbabile che Domenico avesse intenzione di assistere a uno scontro specifico, egli ha brillantemente evocato il tumulto e la confusione di una battaglia all'antica. Sono state suggerite diverse fonti per la stampa di Campagnola; Hind riteneva che il modello definitivo fosse la Battaglia di Anghiari di Leonardo, un'opera mai completata ma elaborata in disegni e, senza dubbio, cartoni. Il disegno di Leonardo fu talmente celebrato all'inizio del Cinquecento che numerosi artisti ne fecero delle variazioni, alcune delle quali potevano essere a disposizione di Domenico. Secondo altri studiosi l'incisione riflette le idee di Tiziano, che fu incaricato di dipingere un grande quadro di battaglia per il Palazzo Ducale nel 1513; sebbene Tiziano non eseguì il dipinto fino al 1537 (fu poi distrutto nell'incendio del 1577), lavorò ai disegni preliminari fino al 1516. “The Battle of Nude Men is one of Domenico's two largest engravings, and the composition is surely the most complicated and ambitious of the whole group; in the handling of the nudes, the treatment of the landscape, and the frenetic actions of the figures, it is also among his most characteristic designs. Though Domenico is unlikely to have intended a specific encounter, he brilliantly evoked the tumult and confusion of a battle all'antica, much as his Milanese contemporary, the Master of 1515, did in his Battle. Both central Italian and Venetian sources for Campagnola's print have been suggested. Hind and the Tietzes believed that the ultimate model would have been Leonardo's Battle of Anghiari, a work never completed but elaborately prepared in drawings and, undoubtedly, cartoons. Leonardo's design was so celebrated in the early sixteenth century that numerous artists made variations on it, some of which could have been available to Domenico, as Oberhuber has recently argued. According to Suida, however, the engraving reflects the ideas of Titian, who was com missioned to paint a large battle picture for the Doge's Palace in 1513; although Titian did not execute the painting until 1537 (it was subsequently destroyed in a fire of 1577), he did work on preliminary designs until 1516. That Domenico's Battle of Nude Men was indebted to Titian's early plans for this commission is generally discounted for a variety of reasons. Yet we know from a document of 1514 that Titian had prepared modelli for his picture, and although none of these has survived, there is no reason why Domenico, whose closeness to Titian is universally admitted, might not have had access to them or to other studies that no longer exist. It has been objected that Titian would have designed a battle in contemporary costume and in a specific locale, rather than a skirmish of generalized nudes in a wood. But Domenico may have departed from Titian in just those features, and moreover Titian's own drawing for the composition he finally completed in 1537 appears to be populated, for the most part, with nudes. Altho. Battle of naked men; copy after Domenico Campagnola (Hind 4); combat between horsemen and foot soldiers in a forest. Etching on iron, circa 1550, signed in the plate at lower left: 'IERONIMU/S HOPFF/ER' (followed by Hopfer's device). A fairly close etched copy of Campagnola's Battle of Nude Men. The major changes occur in the leaves, which are larger, fleshier, more numerous, and more prominent than in the original; a large bird perched on one of these leaves is added at the upper left. “The Battle of Nude Men is one of Domenico's two largest engravings, and the composition is surely the most complicated and ambitious of the whole group; in the handling of the nudes, the treatment of the landscape, and the frenetic actions of the figures, it is also among his most characteristic designs. Though Domenico is unlikely to have intended a specific encounter, he brilliantly evoked the tumult and confusion of a battle all'antica, much as his Milanese contemporary, the Master of 1515, did in his Battle. Both central Italian and Venetian sources for Campagnola's print have been suggested. Hind and the Tietzes believed that the ultimate model would have been Leonardo's Battle of Anghiari, a work never completed but elaborately prepared in drawings and, undoubtedly, cartoons. Leonardo's design was so celebrated in the early sixteenth century that numerous artists made variations on it, some of which could have been available to Domenico, as Oberhuber has recently argued. According to Suida, however, the engraving reflects the ideas of Titian, who was com missioned to paint a large battle picture for the Doge's Palace in 1513; although Titian did not execute the painting until 1537 (it was subsequently destroyed in a fire of 1577), he did work on preliminary designs until 1516. That Domenico's Battle of Nude Men was indebted to Titian's early plans for this commission is generally discounted for a variety of reasons. Yet we know from a document of 1514 that Titian had prepared modelli for his picture, and although none of these has survived, there is no reason why Domenico, whose closeness to Titian is universally admitted, might not have had access to them or to other studies that no longer exist. It has been objected that Titian would have designed a battle in contemporary costume and in a specific locale, rather than a skirmish of generalized nudes in a wood. But Domenico may have departed from Titian in just those features, and moreover Titian's own drawing for the composition he finally completed in 1537 appears to be populated, for the most part, with nudes. Although the theory that Leonardo was, indirectly, Domenico's source of inspiration need not be discarded, the direct influence of Titian seems more plausible to the present writer. Of course Titian was himself undoubtedly influenced by Leonardo's Battle of Anghiari. Titian's woodcut of c. 1514-15, The Submersion of Pharaoh's Army in the Red Sea should also be compared to Campagnola's battle scene; and a drawing in Chicago of a Battle Scene with Horses and Men, by Domenico himself, is very similar to the engraving though not directly related to it” (cfr. Mark J. Zucker Early Italian Masters in “The Illustrated Bartsch” vol. 25 (Commentary), pp. 510-511, n. 013). “The recent rediscovery of Pisanello's wall paintings in the Palazzo Ducale in Mantua has proved in a spectacular manner how important battle and tournament scenes were in the Renaissance for the decorative programs of princely palaces and public buildings. Battle scenes demanded from the artist great skill in the arrangement of the composition and full mastery of the representation of men and horses in motion. It is not surprising that engravers repeatedly took up the subject: Pollaiuolo produced the Battle of the Nudes, Francesco Rosselli a David and Goliath (H. 1, ?.11.6), and the Master of 1515 a fierce Battle in a Wood (H. 17). The most famous battle pieces of the early sixteenth century were Mi. Cfr.

Descubre cómo utilizar

Descubre cómo utilizar