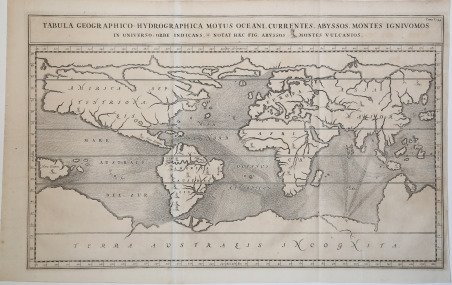

Tabula Geographico-Hydrographica Motus Oceani, Currentes, Abyssos, Montes Igniuomos In Universo Orbe Indicans

Tabula Geographico-Hydrographica Motus Oceani, Currentes, Abyssos, Montes Igniuomos In Universo Orbe Indicans

Formas de Pago

- PayPal

- Tarjeta de crédito

- Transferencia Bancaria

- Pubblica amministrazione

- Carta del Docente

Detalles

- Año de publicación

- 1665

- Lugar de impresión

- Amsterdam

- Formato

- 555 X 400

- Grabadores

- KIRCHER Athanasius

- Idiomas

- Italiano

Descripción

Straordinaria mappa fisica ed idrografica del mondo, raffigurante le correnti oceaniche, profondità marine ed i vulcani. La carta è tratta dal Mundus Subterraneus del Kircher, studioso gesuita, uno dei primi scrittori sui fenomeni fisici della terra. Il Kircher teorizzava che tutti gli oceani della Terra erano connessi tra loro tramite dei tunnel sotterranei che univano oceani e mari. Tra il Mar Mediterraneo, il Mar Nero, il Mar Caspio e il Golfo Persico, Kircher ha teorizzato enormi gallerie e un complesso interscambio di flussi d'acqua. Questi tunnel sono particolarmente noti tra il Mar Nero e il Mar Caspio e tra il Mediterraneo e il Golfo Persico. L'Antartide è rappresentata lungo la parte meridionale della mappa. A nord è raffigurato un grande passaggio aperto a nord-ovest che corre lungo tutta la mappa. Mostra la Nuova Guinea e una suggestione dell'Australia collegata alla terraferma Australsis Incognita. L'Africa è mostrata con una precisione notevolmente maggiore rispetto a molte mappe disegnate centinaia di anni dopo - in particolare per quanto riguarda il Niger e i sistemi fluviali del Nilo. Il Nord America e il Sud America sono entrambi maldestramente raffigurati, il che indica una conoscenza relativamente sommaria del continente. La Corea viene mostrata come un'isola e il Giappone appare come un'unica isola. Kircher entrò nella Compagnia di Gesù il 2 ottobre 1618. Insegnava filosofia e matematica in Würzburg, quando le vittorie degli Svedesi in Germania lo costrinsero a rifugiarsi prima in Francia, ad Avignone, poi a Vienna, donde, nel 1635, fu chiamato alla cattedra di matematiche nel Collegio Romano. Si occupò di filologia (Prodromus coptus, Roma 1636; Lingua aegyptiaca restituta, 1643); di fisica (Ars Magnesia, Würzburg 1631; Specula melitensis, Napoli 1638; Ars magnae lucis et umbrae, Roma 1645); di sacra liturgia (Rituale Ecclesiae aegyptiacae, Roma 1647); di astronomia (Itinerarium extaticum, Roma 1655); di storia naturale (Mundus subterraneus, Amsterdam 1665); di matematica (Organum mathematicum, Würzburg 1668); di musica (Musurgia universalis, Roma 1660; Phonurgia nova, Kempten 1673) e d'altro. Tentò anche l'egittologia, cui appartengono i tre volumi intitolati Oedipus Aegyptiacus (Roma 1652), con i quali credette d'avere scoperto la chiave per l'interpretazione dei geroglifici. Voltosi allo studio della civiltà cinese diede in luce la China monumentis qua sacris qua profanis. illustrata (Roma 1667). Il Kircher ha pure un posto ragguardevole nella storia della scienza geografica, non tanto per le ardite e spesso astruse ipotesi formulate (specialmente nel Mundus subterraneus) a spiegare taluni fenomeni fisici, come la circolazione superficiale e sotterranea delle acque, quanto per la raccolta, anche se indigesta e non elaborata, di dati e di fatti su paesi lontani, che egli ebbe da viaggiatori e missionari gesuiti; a lui spetta il merito di aver delineato il primo abbozzo di carta delle correnti marine, e anche quello di aver richiamato l'attenzione sui fenomeni, che oggi diciamo carsici, pur avendo raccolto e divulgato a questo riguardo molte notizie fantastiche e stravaganti, che del resto erano generalmente credute al tempo suo. Il Kircher è anche autore di opere corografiche d'indole storico-geografica, tra le quali la più notevole è forse il suo Latium (1671). Fu pure solerte raccoglitore di antichità classiche, cristiane, orientali e dell'America Meridionale. Dei cimelî da lui raccolti si formò il museo che porta il suo nome, e si conserva nel Collegio Romano (Museo Kircheriano, ora preistorico ed etnografico). Incisione in rame, finemente colorata a mano, in eccellente stato di conservazione. Extraordinary map, both form the physical and hydrographic point of view, depicting ocean currents, volcanoes and deep-sea chasms. The map is taken from Kircher’s Mundus Subterraneus . The Jesuit scholar, Athanasius Kircher, was one of the first compilers of semi-scientific knowledge about the physical features of the world. This map expounds on Kircher's theories by noting the abysses and the currents they create as well as the locations of the world's known volcanoes. Between the Mediterranean Sea, the Black Sea, the Caspian Sea, and the Persian Gulf, Kircher theorized massive tunnels and a complex interchange of water flows. These tunnels are noted most particularly between the Black and Caspian Sea and between the Mediterranean and the Persian Gulf. Antarctica is shown along the southern part of the map. In the North a great open northwest passage is depicted running all the way across the map. Shows New Guinea and a suggestion of Australia attached to the 'Australsis Incognita' mainland. Africa is shown with considerably greater accuracy than many maps drawn hundreds of years later – particularly with regard to Niger and Nile River Systems. North America and South America are both wildly malformed, indicating a relatively sketchy knowledge of the continent. Korea is shown as an Island and Japan appears as only a single island.Published in a Dutch edition of Kircher's famous Subterranean World by Johann Waesberger. Kircher entered the Society of Jesus on October 2, 1618. He was teaching philosophy and mathematics in Würzburg, when the victories of the Swedes in Germany forced him to take refuge first in France, in Avignon, then in Vienna, whence, in 1635, he was called to the chair of mathematics in the Colleggio Romano. He dealt with philology (Prodromus coptus, Rome 1636; Lingua aegyptiaca restituta, 1643); physics (Ars Magnesia, Würzburg 1631; Specula melitensis, Naples 1638; Ars magnae lucis et umbrae, Rome 1645); sacred liturgy (Rituale Ecclesiae aegyptiacae, Rome 1647); of astronomy (Itinerarium extaticum, Rome 1655); of natural history (Mundus subterraneus, Amsterdam 1665); of mathematics (Organum mathematicum, Würzburg 1668); of music (Musurgia universalis, Rome 1660; Phonurgia nova, Kempten 1673) and more. He also attempted Egyptology, to which belong the three volumes entitled Oedipus Aegyptiacus (Rome 1652), with which he believed he had discovered the key to the interpretation of hieroglyphics. Turning to the study of Chinese civilization he gave birth to China monumentis qua sacris qua profanis. illustrata (Rome 1667). Kircher also has a notable place in the history of geographic science, not so much for the bold and often abstruse hypotheses he formulated (especially in Mundus subterraneus) to explain certain physical phenomena, such as the surface and subterranean circulation of water, but for the indigestible and unelaborated collection of data and facts about distant countries that he had from Jesuit travelers and missionaries; to him is due the credit of having outlined the first sketch of a map of sea currents, and also that of having called attention to the phenomena, which today we say karst, although he collected and divulged in this respect many fantastic and extravagant reports, which, moreover, were generally believed in his time. Kircher is also the author of chorographic works of a historical-geographical nature, among which the most notable is perhaps his Latium (1671). He was also a diligent collector of classical, Christian, Oriental and South American antiquities. Of the relics he collected, the museum that bears his name was formed and is preserved in the Roman College (Kircherian Museum, now the Prehistoric and Ethnographic Museum). Etching with fine later hand colour, ' in excellent condition. Cfr. Shirley, The Mapping of the World, 459.