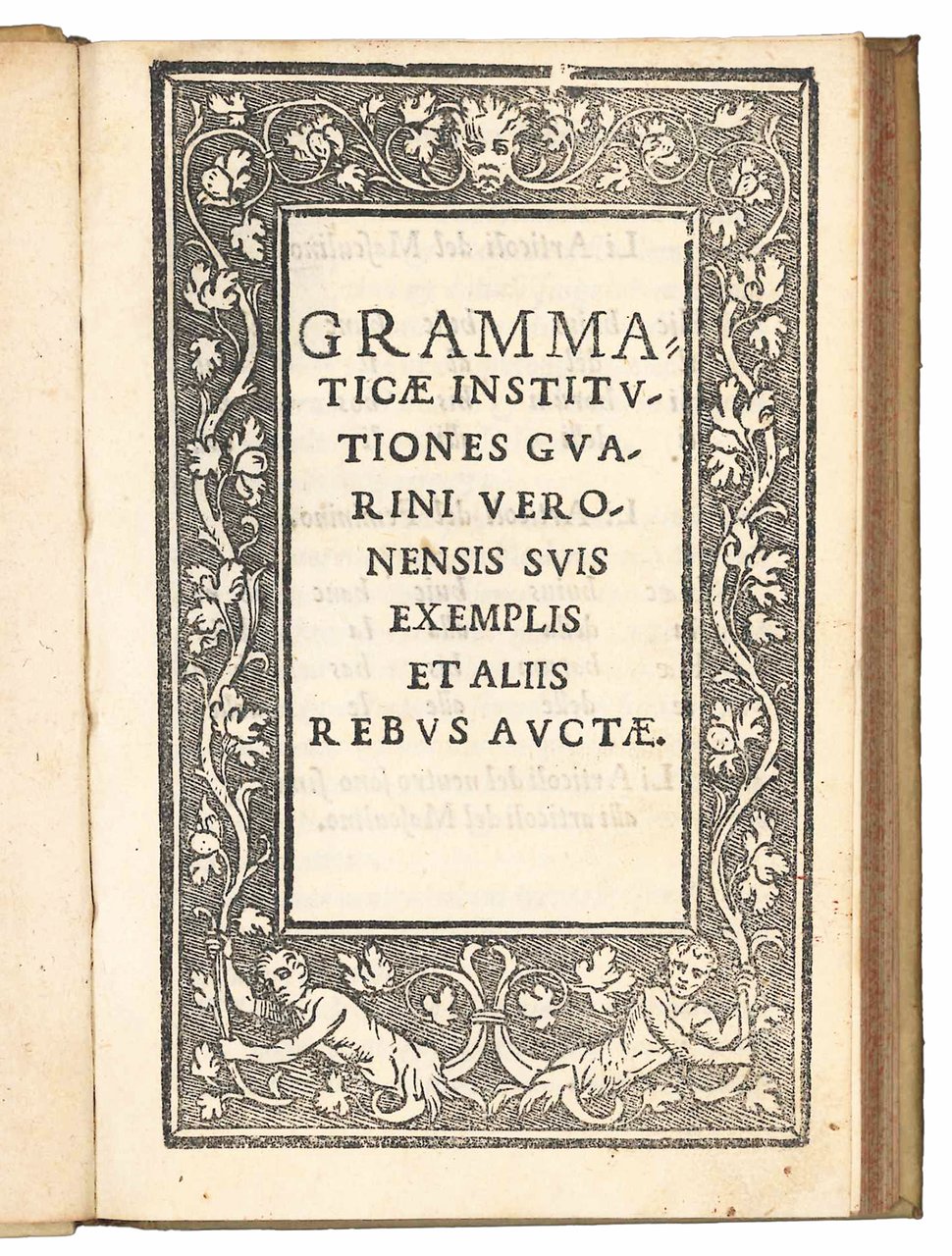

Grammaticae institutiones Guarini Veronensis suis exemplis et aliis rebus auctae

Grammaticae institutiones Guarini Veronensis suis exemplis et aliis rebus auctae

Payment methods

- PayPal

- Credit card

- Bank transfer

- Pubblica amministrazione

- Carta del Docente

Details

- Year of publication

- [not after 1539]

- Place of printing

- Venezia

- Author

- GUARINUS VERONESIS (Guarino Guarini, 1370-1460)

- Publishers

- Bernardino Vitali

- Keyword

- Quattro-Cinquecento

- State of preservation

- Good

- Languages

- Italian

- Binding

- Hardcover

- Condition

- Used

Description

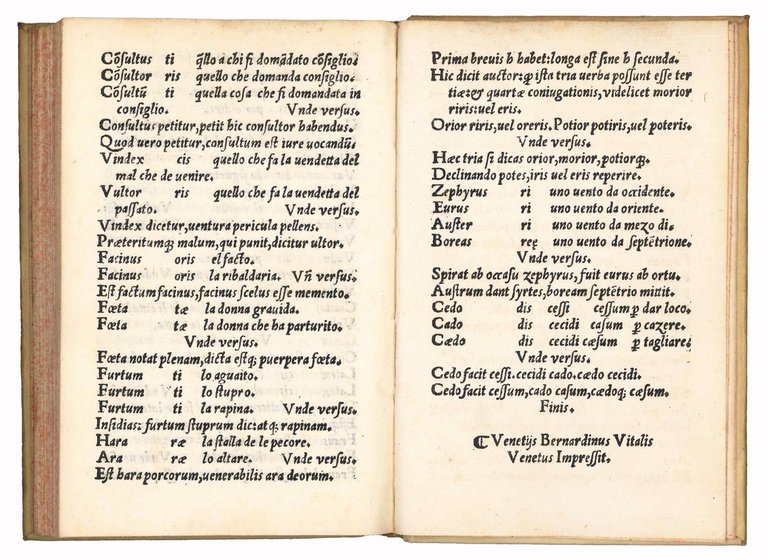

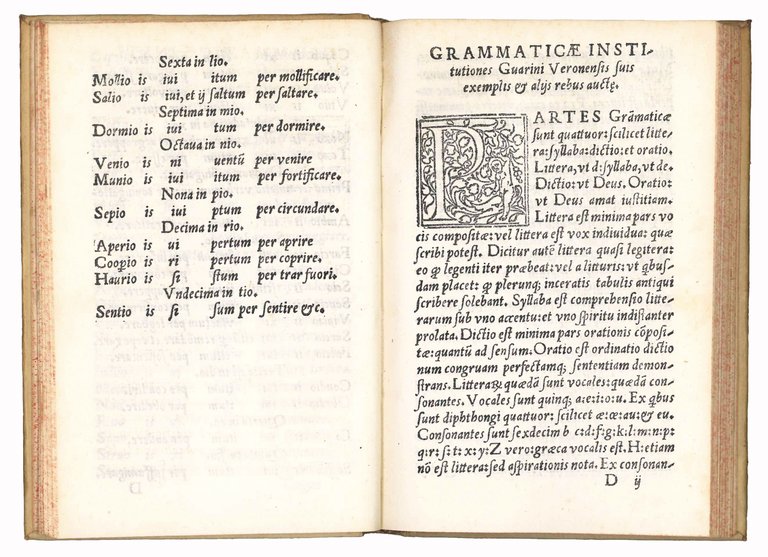

8vo (150x98 mm). [84] leaves. Collation: A8 B-V4. Title page within a woodcut border. Woodcut decorative initials. Colophon at l. V4r. Leaf V4v is a blank. Italic type. 18th-century stiff vellum, morocco lettering piece on spine, red sprinkled edges. Bookplate Libreria Rappaport from Rome on the front pastedown. A very good copy.

Extremely rare 16th-century edition of Guarinus's Regulae grammatices, a canonical text used in all humanistic schools for the teaching of Latin, written in 1418 and first published in 1470.

“Renaissance grammar really began with the appearance of the Regulae grammaticales of Guarino of Verona, written in Venice and first mentioned in a letter of January 1418. Guarino's Regulae kept some traditional content, purged other material, and presented the whole in an innovative format. The combination had enormous influence in the Italian Renaissance […] Guarino broke with the past in several ways. The first, obvious, point is that he wrote his own manual. He must have found the previous texts wanting, a significant conclusion in itself. Second, he purged much medieval syntactical material. For example, he did not use such common medieval grammatical terms as suppositum for subject and appositum for predicate, and he generally simplified. Since Guarino knew well the medieval tradition, his decision to purge indicated a partial rejection of the past. And he eliminated a great deal: the text of the Regulae was only one-fourth to one-third as long as most medieval manuals. Fifteenth- and sixteenth-century printed editions usually contained thirty-six, forty, or forty-eight pages in a small octavo format (10x15 cm.). Guarino handled in a few sentences material to which medieval grammarians devoted pages. Purgation became revolutionary when compared with the normal medieval and Renaissance habit of accretion. For example, commentaries on texts grew as scholar after scholar added glosses without eliminating previous matter. Guarino's grammar liberated the student from some of the grammatical details and complex terminology that medieval students had to learn. Third, Guarino innovated through reorganization. In a field in which the body of fundamental material changes little, Guarino's organization of the content seems more direct and streamlined than that of his predecessors. This admittedly is a subjective judgment, but the format of the printed editions supports the judgment. Humanists and teachers approved of Guarino's Regulae. About forty surviving manuscripts are known, as well as at least forty-six Italian incunabular printings. Another twenty-seven sixteenth- and seven-teenth-century Italian printings have been located. The known surviving post-1500 printings are probably only a small part of the total number of editions issued. Editors added new material, another sign of approval. Imitations appeared, as did versions that falsely claimed to be the Regulae. Teachers and pupils used Guarino's text continuously through the first half of the seventeenth century. Given the strength of tradition in the field of Latin grammar, Guarino's achievement in writing a widely adopted new manual testified to his importance. The Regulae alone confirmed his stature as a major pedagogical force of the Renaissance” (P.F. Grendler, Schooling in Renaissance Italy, Baltimore-London, 1989, pp. 167-169).

“Guarino Guarini (Guarinus Veronensis) was born in Verona. After initial studies at Verona he moved to Padua, where he studied the notarial arts and from 1392 the humanities under Giovanni di Conversino da Ravenna and Pier Paolo Vergerio the Elder. By 1403 he was in Venice, where he taught grammar. He met the Greek teacher Manuel Chrysoloras, whom he followed to Constantinople in 1403. He studied in Constantinople and Greece until 1408, returning to Venice and Verona in 1409. In 1410 he went to Bologna, where he met Poggio Bracciolini and Leonardo Bruni, then attached to the papal curia. On the recommendation of Bruni, Guarino was