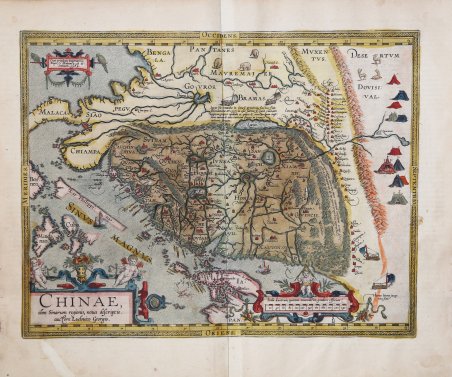

Chinae, olim Sinarum regionis, nova Descriptio

Payment methods

- PayPal

- Credit card

- Bank transfer

- Pubblica amministrazione

- Carta del Docente

Details

- Year of publication

- 1584

- Place of printing

- Anversa

- Size

- 470 X 370

- Engravers

- ORTELIUS Abraham

Description

La carta della Cina di Ortelius è tratta direttamente dai resoconti del cartografo portoghese Luis Jorge de Barbuda (Ludovicus Georgius), che aveva realizzato una carta manoscritta della Cina, pervenuta a Ortelius tramite Arias Montanus. Pubblicata per la prima volta nel 1584, rappresenta la prima mappa stampata incentrata sulla Cina e la prima a illustrare la Grande Muraglia. Con i suoi tre ricchi cartigli ornamentali e le numerose illustrazioni di rifugi indigeni, mezzi di trasporto e animali, è tra le carte più decorate di Ortelius. Al momento della sua apparizione, questa mappa era di gran lunga la più accurata rappresentazione della regione mai realizzata. Il Giappone è rappresentato su una curiosa proiezione curva che ricorda le carte portoghesi dell'epoca, con Honshu sezionato lungo la linea del lago Biwa. La Grande Muraglia è mostrata, ma solo in una sezione relativamente piccola, e la sua lunghezza è notevolmente sottostimata. Le "yurte" dei Tartari sono disseminate nelle pianure e nelle steppe dell'Asia centrale e orientale. I gesuiti portoghesi stabilirono una missione in Cina nel 1577. Sebbene il creatore portoghese della mappa, Barbuda, non fosse un gesuita, le sue fonti per la mappa erano quelle fornite da gesuiti portoghesi. I caratteri cinesi che si trovano nel testo sul retro della mappa sono stati la prima introduzione alla lingua cinese per molti colti europei dell'epoca. Il presente esemplare è il secondo dei tre stati della mappa; include il toponimo "Las Philippinas" sopra il Sinus Magnus. Il toponimo venne aggiunto nell'edizione francese del 1587 del Theatrum Orbis Terrarum. “Until Martino Martini's map of 1655, this map by Luiz Jorge de Barbuda (fl.1575-1599) was the most influential Western portrayal of China. It was used also by Matteo Ricci (1552-1610) as a basis for his world map, Kunyu wanguo quantu (Complete map of the myriad countries of the world), that he prepared for the Wanli Emperor of China in 1602. Although the sixteenth century had seen Portuguese cartographers based in Lisbon or Goa regularly producing innovative maps of Asian regions, these typically provided detailed representation only of the coastal areas with which the Portuguese were most familiar; interior regions were portrayed as empty or filled with text captions and symbols of cities, animals, flags and so on, placed somewhat randomly. Following the establishment of the Portuguese presence in Macao, Lusitanian maps of the 1560s and 1570s showed China's coast with toponyms in Portuguese or in Portuguese transcriptions of Asian names. Examples are the East Asian atlas charts drawn by Portugal-based cartographers such as Diogo Homem (1561), Lázaro Luís (1563), or Sebastião Lopes et al. (c.1565), or even the Goa-based Fernão Vaz Dourado (1570). Likewise, Ortelius' own map of the East Indies of 1570 showed far less precision than this Barbuda's map, and its nomenclature was strikingly different. In preparing his map, Barbuda likely has drawn on several kinds of sources: the unusually detailed 1561 map by Velho; Portuguese writings on China, especially those of João de Barros (1496-1570), Gaspar da Cruz (1520-1570) and Melchior Nunes Barreto (c.1520-1571); and maps that arrived in Europe via Macao and Manila. Some of these may have in turn drawn on Chinese sources. In his Third Decade of Asia (Lisbon, 1563), de Barros mentions using translations of Chinese books and maps, among them a cosmography with "maps showing the config ration of the land, and a commentary thereon in the form of an itinerary," that were prepared for him by a cultured Chinese servant. Both da Cruz and Barre visited Macao and Guangzhou during their time in Asia. Bartolomeu Velho was a cartographer who, like Barbuda, worked in Lisbon and went to Spain in the 1570s. The China of his Asia chart, although not as detailed as Barbuda's, does indeed provide some information on the interior of China. The Great Wall is there, accompanied by a row o. Ortelius' map of China is taken directly from the accounts of Portuguese cartographer Luis Jorge de Barbuda (Ludovicus Georgius), who had made a manuscript map of China, which came to Ortelius through Arias Montanus. First published in 1584, it represents the first printed map focusing on China and the first to illustrate the Great Wall. With its three rich ornamental cartouches and numerous illustrations of indigenous shelters, means of transportation and animals, it is among Ortelius' most ornate maps. At the time of its appearance, this map was by far the most accurate depiction of the region ever made. Japan is depicted on a curious curved projection reminiscent of Portuguese maps of the time, with Honshu dissected along the line of Lake Biwa. The Great Wall is shown, but only in a relatively small section, and its length is greatly underestimated. Tartar "yurts" are scattered across the plains and steppes of Central and East Asia. Portuguese Jesuits established a mission in China in 1577. Although the map's Portuguese creator, Barbuda, was not a Jesuit, his sources for the map were those provided by Portuguese Jesuits. The Chinese characters found in the text on the back of the map were the first introduction to the Chinese language for many educated Europeans of the time. The present example is the second of the three states on the map; it includes the toponym "Las Philippinas" above SINUS MAGNUS. The toponym was added in the 1587 French edition of Theatrum Orbis Terrarum. “Until Martino Martini's map of 1655, this map by Luiz Jorge de Barbuda (fl.1575-1599) was the most influential Western portrayal of China. It was used also by Matteo Ricci (1552-1610) as a basis for his world map, Kunyu wanguo quantu (Complete map of the myriad countries of the world), that he prepared for the Wanli Emperor of China in 1602. Although the sixteenth century had seen Portuguese cartographers based in Lisbon or Goa regularly producing innovative maps of Asian regions, these typically provided detailed representation only of the coastal areas with which the Portuguese were most familiar; interior regions were portrayed as empty or filled with text captions and symbols of cities, animals, flags and so on, placed somewhat randomly. Following the establishment of the Portuguese presence in Macao, Lusitanian maps of the 1560s and 1570s showed China's coast with toponyms in Portuguese or in Portuguese transcriptions of Asian names. Examples are the East Asian atlas charts drawn by Portugal-based cartographers such as Diogo Homem (1561), Lázaro Luís (1563), or Sebastião Lopes et al. (c.1565), or even the Goa-based Fernão Vaz Dourado (1570). Likewise, Ortelius' own map of the East Indies of 1570 showed far less precision than this Barbuda's map, and its nomenclature was strikingly different. In preparing his map, Barbuda likely has drawn on several kinds of sources: the unusually detailed 1561 map by Velho; Portuguese writings on China, especially those of João de Barros (1496-1570), Gaspar da Cruz (1520-1570) and Melchior Nunes Barreto (c.1520-1571); and maps that arrived in Europe via Macao and Manila. Some of these may have in turn drawn on Chinese sources. In his Third Decade of Asia (Lisbon, 1563), de Barros mentions using translations of Chinese books and maps, among them a cosmography with "maps showing the config ration of the land, and a commentary thereon in the form of an itinerary," that were prepared for him by a cultured Chinese servant. Both da Cruz and Barre visited Macao and Guangzhou during their time in Asia. Bartolomeu Velho was a cartographer who, like Barbuda, worked in Lisbon and went to Spain in the 1570s. The China of his Asia chart, although not as detailed as Barbuda's, does indeed provide some information on the interior of China. The Great Wall is there, accompanied by a row of mountains; a large lake is depicted in the northwest, with a legend describing a flood that engulfed seven towns and 153 settle. Cfr.