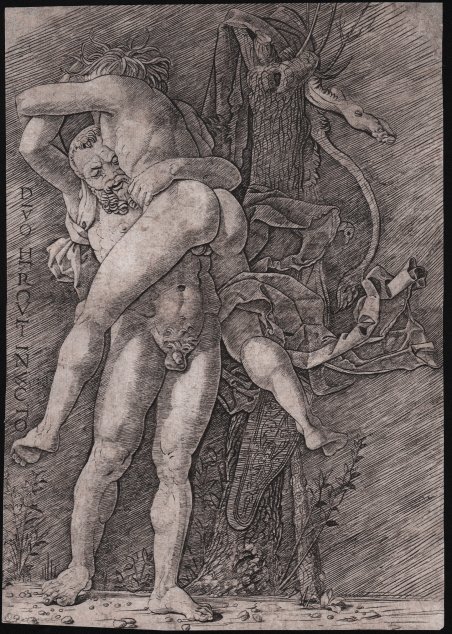

Ercole e Anteo

Payment methods

- PayPal

- Credit card

- Bank transfer

- Pubblica amministrazione

- Carta del Docente

Details

- Year of publication

- 1497

- Size

- 195 X 280

- Engravers

- Primo Incisore

Description

Bulino, 1497 circa, privo di firma. La composizione deriva dagli affreschi del Mantegna per la Camera degli Sposi (nelle cronache chiamata Camera Picta) nel castello di San Giorgio a Mantova; il tema delle fatiche di Ercole era uno dei più popolari dell’arte del Rinascimento, in particolare in quella del Mantegna e della sua scuola. Oltre a questo lavoro e agli affreschi, ci sono pervenuti un disegno, conservato agli Uffizi, altre due incisioni della scuola e due firmate da Giovanni Antonio da Brescia. L’opera rappresenta uno dei lavori di maggior qualità tra le incisioni della cerchia del Mantegna, molto vicino alla tecnica del Maestro. Recenti studi di David Landau e Susan Boorsch assegnano la paternità dell’opera ad un pittore, denominato “Primo Incisore”. La stampa raffigura Ercole che lotta con Anteo, il gigante che traeva la propria soverchiante forza dal contatto con il suolo della madre Gea, la dea Terra: Ercole afferra Anteo frontalmente e lo tiene sollevato, unico modo, come comprende l'eroe, per neutralizzarne la forza e soffocarlo. Sul lato sinistro dell'incisione si legge «DIVO HERCULI INVICTO», un'iscrizione verticale nella quale le lettere sono alternativamente disposte diritte e ruotate di novanta gradi. Si è proposto di riconoscere in questa dedica, ricorrente anche in stampe mantegnesche non legate al mito di Ercole, un omaggio ad Ercole I d'Este, duca di Ferrara dal 1471 al 1505 e padre di Isabella d'Este, per il quale l'uso dei termini «divus» e «invictissimus» risulta attestato da iscrizioni su alcune monete e medaglie del tardo Quattrocento. Nella mostra londinese del 1992, Suzanne Boorsch inserisce la stampa nel corpus di incisioni realizzate da un maestro appartenente alla stretta cerchia mantegnesca, che la studiosa battezza "primo incisore" (premier engraver) per sottolinearne la fedeltà alla tecnica incisoria di Mantegna e la notevole abilità. Già Hind aveva del resto riconosciuto nell'Ercole e Anteo una tecnica esecutiva molto prossima a quella di Mantegna in stampe come la Zuffa degli dèi marini, esperta nella conduzione del bulino e capace di delicate modulazioni tonali, particolarmente ricche sulle superfici del tronco in ombra alle spalle dei lottatori. La presenza dell'Ercole e Anteo tra le lastre di incisioni che il figlio di Mantegna, Ludovico, ha in casa nel 1510, all'epoca dell'inventario dei suoi beni, mette a suo modo in evidenza la particolare importanza di questa incisione, realizzata sull'altro lato della lastra recante le Quattro muse danzanti. Questa stretta relazione materiale con le Quattro muse danzanti, invenzione che dipende dal Parnaso di Mantegna del 1497 (ora al Louvre), sembra implicare anche per l'Ercole e Anteo una datazione agli anni Novanta del Quattrocento. Tale ambito cronologico risulta inoltre suggerito dalla tipologia stessa delle figure, robuste e muscolose, solidamente inserite nello spazio, per le quali possono evocarsi convincenti termini di confronto con la produzione pittorica del Mantegna tardo, come la grisaille con Davide con la testa di Golia (Vienna, Kunsthistorishes Museum). Per l'identità storica di questo anonimo e dotatissimo incisore, i recenti ritrovamenti documentari, e le notizie già note, sembrano suggerire il nome dell'orafo e incisore Gian Marco Cavalli, impiegato come incisore da Mantegna già nel 1475 e rimasto a stretto contatto col maestro fino alla morte di questi, come prova la sua presenza alla redazione del testamento di Mantegna del 1506. La più evidente fortuna della stampa, tematicamente riconducibile in un più ampio gruppo di disegni e incisioni mantegnesche dedicato alle Fatiche di Ercole, si consuma nella stessa cerchia del pittore. In particolare, Giovanni Antonio da Brescia ne riproduce una copia a bulino in controparte, ottenuta sembra non direttamente dalla lastra dell'incisione bensì trasferendo su una nuova lastra i contorni traforati di una versione a stampa della composizione (cf. Hercules and Antaeus; Antaeus seen from behind and held by the waist; a tree trunk in the background Engraving, 1497 circa, lettered vertically down left side: 'DIVO HERCULI INVICTO'. The composition has been realized after the drawings of Mantegna for the Camera degli Sposi (also known as Camera Picta) room, in the Ducal Palace, Mantua; the theme of Hercules was one of the most popular during the Reinassance, particularly for Mantegna and his workshop. Apart from this work and the frescoes, there is a drawing and four engravings of the workshop, two signed by Giovanni Antonio da Brescia. This work can be considered one of the best quality examples ever realized in the circle of Mantegna, and very close to the technique of the Maestro. In the 1992 London exhibition, Suzanne Boorsch includes the print in the corpus of engravings made by a master belonging to Mantegna's close circle, whom the scholar names "premier engraver" to emphasize his fidelity to Mantegna's engraving technique and remarkable skill. For the historical identity of this anonymous and highly gifted engraver, recent documentary findings, and already known information, seem to suggest the name of the goldsmith and engraver Gian Marco Cavalli, who was employed as an engraver by Mantegna as early as 1475 and remained in close contact with the master until his death, as evidenced by his presence at the Mantegna's testament of 1506. “Mantegna apparently designed at least two different cycles of the deeds of Hercules. One comprises six frescoes on the ceiling of the Camera degli Sposi, while another is recorded in a document of 1463 which states that an artist named Samuele painted a room dedicated to Hercules using drawings by Mantegna. Two basic versions of the Hercules and Antaeus scene by Mantegna are known. The composition used in the fresco of the Camera reappears in a number of variations, including several engravings and a drawing recently attributed to Mantegna. All of these versions show the figure of Hercules in a striding posture, holding Antaeus from behind or from one side, so that both the hero's arms cut into the midriff of his victim. Antaeus's legs are spread in a scissors movement. As Mezzetti (cfr. Andrea Mantegna, Catalogo della Mostra, Venezia 1961) points out, this composition is quite close to antique models, such as the sculpture group in Marbury Hall, Smith Barry Collection. The figures' great activity, their rather slender proportions, and their lack of volume are all typical of Mantegna's early works in Mantua. The version recorded in our engraving is quite different and clearly later. Hercules' pose is more solid and more suggestive of weight, and both he and his opponent are more massive and three-dimensional figures. Because of these qualities, the group is closer to antique prototypes, both formally and spatially, than is the earlier version. In fact, Mezzetti convincingly compares our engraving with a Hellenistic statue of Hercules and Antaeus, a work which Mantegna could have seen in Rome, that displays a similar solidity and massiveness. For this reason Mezzetti dates the engraving near Mantegna's return from Rome in 1490. The dating of the composition to the post-Roman period is also supported by comparisons with the late grisaille panels, which were surely designed by Mantegna, although their execution is in dispute. The panel of David with the Head of Goliath is a particularly good comparison for the proportions of the figures, the musculature, strongly defined by shading and bright highlighting, the use of space, and even the type of hair found on Antaeus and Goliath. The Vestal Tuccia is especially close to the engraving in the type of drapery used. The manner of engraving, employing fine shading strokes within heavy outlines, is typical of the late school engravings and adds further support to a dating in the 1490s. As Hind has noted, the technique is most like Mantegna's own. The sharp demarcation between . Cfr.